Erich Neumann

His theories about mythology and religion examined by Stefan Stenudd

In 1933, he attended a seminar held by Carl G. Jung in Berlin, and later the same year went to Zürich for seven months to be analyzed by him.[1] Jung held Neumann in high regard, which is evident in the foreword he wrote in the latter’s book The Origins and History of Consciousness, praising his achievement, “he arrives at conclusions and insights which are among the most important ever to be reached in this field.”[2] Before meeting with Jung, he had developed an interest in Judaism, in particular Hasidism and its mysticism connected to the Kabbalah, which stayed with him through his life.[3] His attraction to mystical thought was evident already in his 1927 dissertation in philosophy, about the early 19th century philologist Johann Arnold Kanne, who had used a very speculative etymology to find a primordial mythology.[4]

New Ethics in the ShadowNeumann’s early literary projects were within fiction and poetry, but in 1949 he published two books with psychological themes, both containing respectful forewords by Jung. The first,Tiefenpsychologie und neue Ethik (Depth Psychology and a New Ethic), dealt with the horrifying evil exposed in World War II, which he related to the Jungian idea of the shadow, the dark side of the personality. When this entity within us is ignored, a reaction is unavoidable, and we fall much like Icarus after flying too high:

Certainly, society’s moral demands on its citizens, some outspoken and some not, can be a straitjacket strapped so tightly that people nearly suffocate. Conformity can easily go too far, allowing no room for personal deviation, not even accepting that the human being is equipped with any urges regarded as immoral. As if perfect adaption to social demands is human nature. That won’t work, and the cost for insisting on it is high for individuals as well as society. It leads to discomfort, unrest, and brutality. Whether that has anything to do with a shadow entity residing in an unconscious, though, is questionable, and so is basing a cure for society and its people on such a concept. People have needs. Some of them are unacceptable to society, but others might just as well be allowed or at least disregarded. In every society, there is continuous interaction between what is expected of people and with what they are unable to comply. There is compromise everywhere. It is not unconscious. People know when they are suppressed, and what causes their inhibitions as well as the instances when they act in spite of them. Since these processes are known and considered in any society, there is little hope that introducing an unconscious shadow into the mix will fix things. The delicate balance between social demands and personal needs will still be continuously recalibrated.

Consciousness through MythologyThe second book of the same year, which made much more of an impression on Jungians, was Ursprungsgeschichte des Bewusstseins (The Origins and History of Consciousness), where he used a number of mythological components to describe stages in the evolution of consciousness, both in mankind as a whole from primeval times and in each person’s development from infancy and on, since “the individual ego consciousness has to pass through the same archetypal stages which determined the evolution of consciousness in the life of humanity.”[7]Before this process begins, the human mind is unconscious, or as Neumann puts it, “the ego is contained in the unconscious.”[8] The awakening of consciousness comes in stages, shown by archetypes. Since the archetypes reside in the collective unconscious, that must be the engine in this process. Neumann refers to the content of the collective unconscious as transpersonal, as opposed to individual. The archetypes and their meanings are rooted in us all, but Neumann firmly denies that historical events can be inherited, no matter how unique or recurrent they are, “for up to the present there has been no scientific proof of the inheritance of acquired characteristics.”[9] He uses this argument to dismiss a central theory of Sigmund Freud, without mentioning his name. He doesn’t need to, since it is obvious:

There are additional peculiarities with Neumann’s theory about the origins of consciousness. Starting all the way back to primordial times, he finds relevant archetypes in creation myths. He compares the development since that distant beginning with the child growing up, but it is strangely unclear if he refers to the actual past or just the transpersonal images of it, residing in the unconscious of us all. He must mean the latter, or his understanding of scientific cosmogony is lacking, indeed. But then, how did the archetypes take form, since mankind did not appear for a few billion years after our world was formed? From where did they get a symbolic imagery describing the creation of the world? Neumann doesn’t discuss this in his book, but the plausible answer would be that the archetypes are in no way about the creation, only about human growth of consciousness. Still, he suggests that primeval man was wondering about the mysteries of the world:

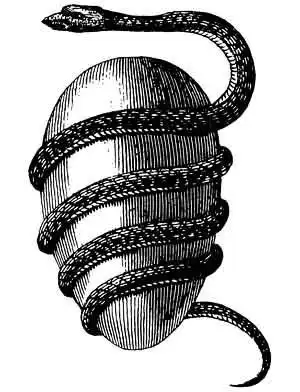

For example, he mentions Egyptian creation texts where the sole primordial deity gives birth to offspring by masturbating into his mouth and spitting it out. Neumann interprets it symbolically, but to ancient Egyptians it was a reasonable explanation to how the first deity all alone could multiply — by self-impregnating. Nothing unconscious is needed to explain the myth.[11] Mythology is full of clever solutions to the problem of origin, what was first and how the rest of the world came into being. It was something our ancestors enjoyed contemplating, as we still do. Neumann does not allow for this, claiming about early man that “abstract questions of this kind were wholly alien to his consciousness.”[12] According to Neumann, it is still not much the “primitive” understand, not even the basics of procreation: “Many primitive peoples do not recognize the connection between sexual intercourse and birth.” He gives no source to this absurd claim. As for his archetypes at the dawn of creation, there is a primary one — the circle, which is “allied” to the sphere and the egg, but Neumann links it mainly to the ouroboros, the circular image of a snake biting its own tail. To him it stands for “the Primal Deity who is sufficient unto himself,” but it also represents the maternal womb, the union of masculine and feminine that are the world parents, and even the primal ocean.[13] Thereby, Neumann combines ingredients from several different creation myths into one. That is hard to find in mythology. A primal entity can be a world egg, or the womb of one deity who gives birth to the world, or an initial couple being its parents, or a primordial sea out of which the world emerges — but not all in one myth. And the ouroboros is utterly rare in creation myths, if there is even one where it is the primal being. There are similarities in creation myths, but also many differences. They cannot be molded into one. Neumann’s creation process towards consciousness goes through several steps, represented by archetypal deities that seem to be essentially the same one in stages of metamorphosis. There is the Great Mother, about whom he would soon publish a separate book, the separation of the World Parents, then the Hero slaying his mother and father, whereby he gets his treasure. This treasure is a captive liberated by the hero killing a dragon of some sort, like the valiant knight saving the princess in many fairy tales. But this captive is to be understood symbolically, as “something within — namely the soul herself.” By freeing the captive, the hero is really freeing his own soul. The puzzle of the archetypes at play shows the way for anyone to accomplishing this, since “the hero myth is never concerned with the private history of an individual, but always with some prototypal and transpersonal event of collective significance.”[14] Neumann’s view on the soul is peculiar. He claims its reality is felt by all, but completely misunderstood by primitive man:

Accessing the whole world of mythology, it is easy to find similarities or patterns when picking a few. Many anthropologists have been known to do the same, especially in the 19th and early 20th centuries. In the vast mythological material assembled, anything could be argued about the meaning and function of mythology as a whole, by selecting examples carefully. But there are always deviations from the suggested norm, and usually they are in majority. It is a hopeless task trying to prove any theory that claims all mythology to be basically the same, since that is just not the case. The same problem is obvious in Neumann’s writing. It does not hold up to close inspection, nor do the sources he uses to prove his case. Jung was the source that Neumann leaned on the heaviest, referring to his texts as proof of claims about the archetypes and the human psyche. But Jung did not present any solid evidence of his theories. They were just speculations, and the patterns he saw were indeed questionable. As for mythology and its interpretation, Neumann frequently used the writing of Swiss 19th century anthropologist Johann Jakob Bachofen, who had theories about early stages of society and linking them to certain significant deities. In his book Das Mutterrecht (Mother Right) from 1861, he claimed that in the distant past there had been a stage of matriarchy, basing much of society as well as religion on motherhood, later replaced by patriarchy.[18] An interesting theory, certainly, but again speculation, lacking convincing evidence. As for Neumann’s theory about archetypes from the collective unconscious gradually giving people consciousness, it needs first of all to show that they lacked it previously. It is a strange presumption. We are biological creatures, and the brain has been formed by the same slow evolutionary process as the rest of the body. Consciousness, as in self-awareness, is a consequence of how our brains have evolved, and it may have been with us for very long. After all, it is an essential resource in keeping ourselves alive. And as long as we have had that resource, we have used it. Otherwise, we would not have it. Babies might not be self-conscious already at birth, but it is sure to come — without the need of archetypal stimulation. Still, comparing creation myths with human development, the species as well as the individual, is an interesting thought experiment. They share some elementary components, such as describing a birth of sorts, and a growth in both size and complexity. Well, that’s about it. But the claim that creation myths are about humans and not at all about the world is erroneous. It is indicated already by the fact that there are many creation myths where humans enter very late, and often fail to play any significant role. Most of all, the cosmogony of those myths makes it quite clear that they primarily express speculations about how the world began and why it is as it is. The perspective is one of humans as spectators instead of main players. So, it is not really about us.

Woman as an ArchetypeNeumann’s other major book is The Great Mother, which he wrote in German (Die große Mutter. Der Archetyp des großen Weiblichen) but its first publication was the English translation of it in 1955.As the title states, the book is about the archetype of the Great Mother, who was also treated at length inThe Origins and History of Consciousness. But here the subject is expanded, and so are the examples and different appearances of this archetype. He explains its vast importance:

Woman is described as an intricate, mysterious being of vast archetypal importance, whereas man is little more than synonymous to humankind, as if only he belongs to the species and she is a mythical creature, a superhuman deity. A flattering description at first, but excluding at length. Neumann widens the symbol of the vessel to point to the human body’s interior, what it carries inside, which is “archetypally identical with the unconscious.”[22] So, in this sense both men and women are vessels. Still, it applies particularly to woman:

Neumann first writing was within fiction and poetry. This passion might explain his interest in the fantastic landscape of Jungian psychology, and his way of treating the subject in his books — like fantastic stories, full of fantastic creatures steering humans in hidden ways, some towards tragedy and some towards a happy ending. Neumann turned depth psychology into a fairy tale. He might even have approved of this analogy.

Notes[1] Lance S. Owens,

C. G. Jung and Erich Neumann: The Zaddik, Sophia and the

Shekinah

, PDF 2017, p. 4.

[2] Erich Neumann, The Origins and History of Consciousness,

transl. R. F. C. Hull, New York 1970 (originally published in

German 1949), p. xiv.

[3] Owens 2017, p. 4.

[4] Erich Neumann,

Johann Arnold Kanne: Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der mystischen

Sprachphilosophie

, University of Erlangen 1927.

[5] Erich Neumann, Depth Psychology and a New Ethic, transl.

Eugene Rolfe, London 1969 (the original was published in 1949), p.

43.

[6] Ibid., 79f.

[7] Erich Neumann, The Origins and History of Consciousness,

transl. R. F. C. Hull, New York 1970 (originally published in

German 1949), p. xvi.

[8] Ibid., p. 5.

[9] Ibid., xxi.

[10] Ibid., p. 7.

[11] Ibid., p. 19.

[12] Ibid., p. 13.

[13] Ibid., pp. 11, 13, 23.

[14] Ibid., pp. 196f.

[15] Ibid., p. 209.

[16] Ibid., p. 210.

[17] Ibid., pp. 213ff, 221ff.

[18] Erich Fromm also referred to Bachofen and the matriarchy, inThe Forgotten Language from 1951.

[19] Erich Neumann,The Great Mother: An Analysis of the Archetype, transl.

Ralph Manheim, Princeton 1972 (first edition 1955), p. 3.

[20] Ibid., p. 25.

[21] Ibid., p. 39.

[22] Ibid., p. 40.

[23] Ibid., p. 42.

[24] Ibid., p. 83.

Jungians on Myth and Religion

This text is an excerpt from my book Archetypes of Mythology: Jungian Theories on Myth and Religion Examined, from 2022. The excerpt was published on this website in January, 2023.

MYTH

IntroductionCreation Myths: Emergence and MeaningsPsychoanalysis of Myth: Freud and JungJungian Theories on Myth and ReligionFreudian Theories on Myth and ReligionArchetypes of Mythology - the bookPsychoanalysis of Mythology - the bookIdeas and LearningCosmos of the AncientsLife Energy EncyclopediaOn my Creation Myths website:

Creation Myths Around the WorldThe Logics of MythTheories through History about Myth and FableGenesis 1: The First Creation of the BibleEnuma Elish, Babylonian CreationThe Paradox of Creation: Rig Veda 10:129Xingu CreationArchetypes in MythAbout CookiesMy Other WebsitesCREATION MYTHSMyths in general and myths of creation in particular.

TAOISMThe wisdom of Taoism and the Tao Te Ching, its ancient source.

LIFE ENERGYAn encyclopedia of life energy concepts around the world.

QI ENERGY EXERCISESQi (also spelled chi or ki) explained, with exercises to increase it.

I CHINGThe ancient Chinese system of divination and free online reading.

TAROTTarot card meanings in divination and a free online spread.

ASTROLOGYThe complete horoscope chart and how to read it.

MY AMAZON PAGE

MY YOUTUBE AIKIDO

MY YOUTUBE ART

MY FACEBOOK

MY INSTAGRAM

STENUDD PÅ SVENSKA

|

Archetypes of Mythology

Archetypes of Mythology Psychoanalysis of Mythology

Psychoanalysis of Mythology