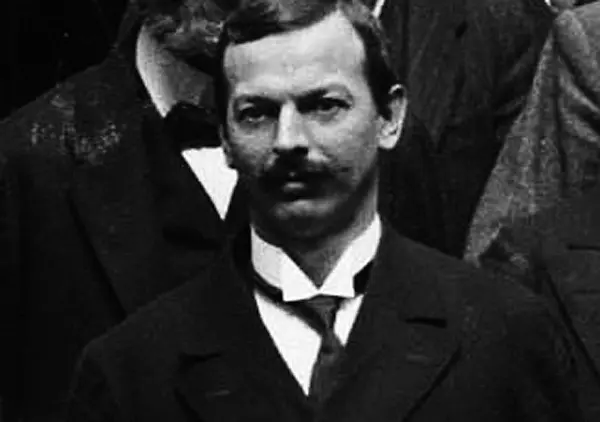

Oskar Pfister

His theories about mythology and religion examined by Stefan Stenudd

In 1908, Pfister visited Sigmund Freud for the first time. They had an ongoing correspondence until 1937, two years before Freud's death. Many of those letters were published in the volume Psychoanalysis and Faith, 1963. As the title emphasizes, the subject in the letters was often, but not exclusively, religion. The atheist and the pastor certainly had their disagreements on this issue, but they remained close friends and Pfister stayed a supporter of Freud's theory of psychoanalysis all through.[2] Pfister had problems being accepted by some other psychoanalysts, though, since he had no formal medical education. This was regarded as a prerequisite — also initially by Freud, but he grew to change his mind. In the introduction to Pfister's book The Psychoanalytic Method from 1913, Freud wrote:

Psychoanalysis for MissionariesIn 1921, Oskar Pfister wrote an article for a German journal on missiology and religious studies (Zeitschrift für Missionskunde und Religionswissenschaft) on how to apply psychoanalysis in missionary work. The English translation of it was two years later included in his book Some Applications of Psycho-Analysis.At that time, psychoanalysis was still new, and far from generally accepted as a science, whereas missionaries had been active around the world for centuries, which led Pfister to ask this rhetorical question:

He continues by describing what it can uncover about religion:

Pfister's idea about the truth revealed by psychoanalysis is not only limited to Christianity, but to the form of it that is his: "Protestant religion, which is free from neurosis."[8] Furthermore, it should be void of the pomp of dogma, and focus on what he regards as its essence: "The spirit of love is everything."[9] He grieves how modern society has corrupted Christianity:

Neurotic ReligionOskar Pfister's firm conviction of his own religion as the only true one, and the ultimate result of psychoanalysis, makes him a flawed theorist on the psychological causes and mechanisms of religion. That cannot be done when excluding his own religion from the study. Still, that is what he does, without even arguing for this omission.He bases his theories on what he calls natural religions, by which he means primitive ones, and regards them as having originated in magic as a method against anxiety, which he separates from fear: "Fear appears only when there is real danger; anxiety without it." It is the fear of the unknown.[10] The theory of religion born out of magic was widespread at his time, explained as a will to control what was really uncontrollable. Anxiety was certainly part of it, but of course there was real danger involved. Life among so-called primitives was not safe. People had many reasons to be scared, and tried magic against both known and unknown threats. As Pfister mentions, magic was also used in efforts to gain things, not just as protection.[11] That has nothing to do with the anxiety of which he speaks. What he adds to the mix is that by time, this behavior became neurotic: "magic and obsessional neurotic rituals are one and the same." He concludes, stressing it with italics:

But that is far from everything religion encompasses, neither Christianity nor any other one. Religions have many functions, which they all more or less share. Pfister is well aware of the complexity of his own faith, but presents nothing that fundamentally separates it from other religions, except his claim that it is the one that is true. He has the burden of proof on that statement, but never presents it. To him, that is just how it is. An amusing example of his bias is found in what he calls the fixation to the father and its influence on religious worship. But what Jesus "in His capacity of profound psychologist" presented as an antidote was God in that role: "God as Father is the greatest help in the fight against the father as god."[12] That may be a different father, somehow, but it increases instead of lessens the father fixation. This is at the core of Freud's idea about how religion emerged: God was an image of the father, a product of the Oedipus complex. Pfister would have benefited from instead focusing on how Jesus transformed the image of that supreme deity from a stern and punishing father into a loving one.

The Illusion of a Future of an IllusionIn 1927, Sigmund Freud's The Future of an Illusion, discussed earlier, was released. To a significant extent, the book was the result of his correspondence with Oskar Pfister on the subject of religion.In a letter to him a few weeks before the book was to be published, Freud expressed his hesitation about the book, as well as his respect for Pfister:

In opposition to Freud's dismissal of religion, Pfister insists on its values — at least when it comes to Protestant Christianity, as it has developed, which is the one of his own conviction. He recognizes the element of neurotic compulsion in religion of which Freud speaks, but mainly in the primitive forms of it, lacking the structure of a church:

There is no end to what good comes out of religion, according to Pfister, and he finds it mostly in Protestant Christianity. For the long listing below, he claims that these feelings are inaccessible to irreligious persons, and it is a lot of which they are deprived:

Religion versus ScienceSigmund Freud's main theme in his book The Future of an Illusion is the conflict between religion and science as opposite approaches to understanding and relating to the world. A good part of Oskar Pfister's text deals with the same polarity.It is a strange one. Comparing religion and science as if interchangeable is questionable, indeed. They are different concepts, different entities, with very little in common. Science is a process by which to explore and explain the world and all its components. It is a method of investigation. Religion, on the other hand, is a way to relate to the world, attaching meaning to it on a personal and social level. It is an attitude towards life. Science is pursued by reason, whereas religion is pursued by emotion. It is possible to apply science to the phenomenon of religion, its manifestations and doctrines, in order to describe it. But it is not a method by which to discard religion, as if it were a scientific theory proven to be false. Religion is neither constructed by nor dependent on scientific validation. Its claims are held to be true among its devotees, which is not the same as establishing facts. It is admittedly subjective. That is, to a great extent, the point of it. Judging religion by its scientific accuracy is as irrelevant as judging science from a religious standpoint. Not that it hasn't been done, repeatedly by both. That may be where they actually meet, since it is usually done by evaluating the consequences of them, what they lead to in people's minds and in society. It is also what both Freud and Pfister focus on in their texts. What Freud means by the illusion is that of religious beliefs, whereas Pfister counters by stating that the blessing of science is just as much an illusion. He puts it rather bluntly, while at the same time showing respect for the pioneer of psychoanalysis:

One of his arguments is that many famous scientists and other admired thinkers were in agreement with religion and science at the same time.[21] He names several of them, such as Descartes, Newton, Darwin, Pasteur, Leibniz, Pascal, Gauss, and even Einstein. But most of those mentioned belonged to a time when Christianity was not only dominant in European culture, but practically compulsory. They may have expressed a different view if they felt at liberty to do so. Even Voltaire treaded quite carefully when speaking about things relating to the dogma of the church. Pfister neglects the same aspect when discussing the arts. He calls religion the sun that pushes forth the most glorious blossom-life of art and goes on to claim: "All great and powerful art is prayer and an offering before God's throne."[22] Among the artists inspired by Christian feeling he names Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo's Pietà.[23] Certainly, religious themes were very common in art works of past centuries, but that was not necessarily from piety of the artist. The church was simply a very wealthy and frequent buyer of art, with a particular taste. Artists could comply or starve, if they were not able to make a living solely from portraits and sculptures of royals and aristocrats. As for Michelangelo's Pietà, its inspiration and sentiment may be any mother grieving her dead son, and Leonardo da Vinci was expressly driven by research into many fields, with the attitude of a scientist also when painting. This is clear in his notebooks, where he discusses many subjects of art and science, but not religion. That does not mean he was an atheist. It would not only be dangerously blasphemous in his days, but also hard for him to fathom. Without a god, the existence of the world and all its creatures would be difficult to explain before the discoveries by Newton and Darwin. A supreme power was assumed. On the other hand, it did not mean that artists worked by divine inspiration. Usually, they were not particularly pious. Leonardo had a practical rather than devotional attitude towards art and God's role in it: "Thou, O God, dost sell unto us all good things at the price of labour."[24] That is comparable to the quote accredited to George Bernhard Shaw about artistic creativity being "ninety per cent perspiration, ten per cent inspiration,"[25] as well as Thomas Edison's opinion about genius being 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration.[26]

Christianity as a Cure of FearIn 1944, sixteen years after the above discussed text, Oskar Pfister published Das Christentum und die Angst, which was translated to English four years later as Christianity and Fear. The book, spanning almost 600 pages, returns to the same subject — that of Jesus as sort of a psychoanalyst and his doctrine one of freeing people from guilt-induced neurosis.The English title's "fear" is somewhat misleading. The German word Angst can indeed be translated so, but as the text points out, the concept intended is closer to anxiety or for that matter the loanword angst as it is used in English. Simply put, it represents, as Pfister uses it, a persistent trepidation about something that is not a concrete or imminent threat. For the emotional response to a threat that is concrete and imminent, Pfister uses Furcht, which is translated to "dread" in the English version.[27] Another possible translation would be "fright," emphasizing its imminence. Pfister regards the two terms as describing different emotions, but that can be debated. What they indicate, as he uses them, are different causes or catalysts to an emotion that may essentially be one and the same — the adrenaline induced high-alert response to danger, real or imagined, taking us to the fight-or-flight mode. It is an essential resource for our survival, which is why it can be triggered when no real or imminent threat appears. As the saying goes: better safe than sorry. The real and imminent threat awakens a response, and when that threat is overcome or avoided, we return to our normal mode. A remaining threat, then, keeps us in the alert mode we experience as trepidation, fear, dread, fright, or whatever we call it. So can the vague impression of a threat we are unable to sufficiently define and therefore also unable to end. If such senses of threat are persistent, according to Pfister, they can lead to neurosis. That is what he sees flawed religions cause. They keep people in a state of fear — fear of a vindictive god, fear of an eternal hell awaiting the deceased, and so on.

LoveAccordingly, his solution is another emotion, namely love. It is the antidote to fear. His primary argument for this is from the Bible, in the First Epistle of John 4:18: "There is no fear in love; but perfect love casteth out fear: because fear hath torment. He that feareth is not made perfect in love." Pfister explains, "fear is thus caused by disturbances of love."[28]But that is not what the Bible quote says. It does not state what is the cause of fear. It simply says that the presence of one excludes the other. Where there is fear there cannot be love, and vice versa. It also says that love is the stronger entity. Where it enters, fear dissolves. That means fear is unable to disturb love. It can only remain where love is absent. Another thing to consider is what may be meant by love — in the Epistle as well as in Pfister's text. That is even more of an enigma than fear. Although it is to Pfister the elixir that can save mankind, he spends significantly less words on it than he does on the concept of fear. He refers to a previous text of his where he defined love, but adds that he wishes to alter it slightly:

Considering the importance he gives this emotion, his perception of it is surprisingly limited. As an example, he mentions that children love sweet fruit and experience a desire to taste it. That is definitely not to love, but to like. Children know the difference. He goes on to speak about a higher level love incorporating aesthetic, ethical, religious and intellectual values. Again, that is not relevant to the emotion itself, but rather to how it is defended. Then he separates love directed to the subject from that to an object. The former is an instrument to increase personal pleasure, which Pfister labels narcissism. The latter is directed towards the interest of others and doing everything for them. Another terminology would be selfish and unselfish love. This may seem like a dismissal of self-love, but in his book Pfister insists repeatedly — in accordance with the famous saying of Jesus to love one's neighbor as oneself — that this love, too, is essential. Rejecting it frequently leads to "a masochistic contraction of the personality."[30] There is also a third kind of love, again describing who or what is loved rather than the nature of the emotion: the love of God, by which he means the Christian devotion to God as Jesus portrayed him. This was a loving God, and his love was of its very own kind, "the sacred love and kindness which he apprehended to be God's innermost nature."[31] This divine love goes beyond what is fathomable:

Nygren and Pfister differ in that the latter would not condemn selfish love, and he regards the polarity argued by Nygren as exaggerated. He points out: "Frequently the Greek eros is a descending and selfless love." He finds support for it in Plato's Symposium, where it is said about the deity Eros: "He is the oldest of the gods and is for us the source of the highest values."[33] Indeed, Eros is a deity who represents something far beyond the mere lust that is often linked to him. In the creation story of Hesiod's Theogony, Eros is one of the first deities to appear and he is given remarkable traits:

Pfister states that the blessing of love, as Jesus promoted it, surpasses the difference between wanting and giving it, so that the good outcome is still reached:

HygieneThe curing of Christian minds through a proper understanding and committing to the love of which Jesus spoke, Pfister speaks of as a religious hygiene. The word hygiene has some complicated connotations, especially in the time and place of Pfister's book, which was 1944 in Europe.That was the year before World War II ended and the concentration camps were displayed to a whole world aghast. They showed the monstrous Nazi application of eugenics, labeled racial hygiene. In 1944 the concentration camps were not yet well known, but the grotesque ideas of racial hygiene were. Oskar Pfister must have been aware of them, but his use of the term hygiene cannot be interpreted as him agreeing with that dreadful application. It is just unfortunate, especially when used in a social setting and not just in the medical sense of personal preventive healthcare. He speaks of the hygiene of religion serving "the cause of social and national hygiene,"[37] and points out that "in the schools too hygiene cannot be neglected."[38] By the end of his book, he states:

In addition, Pfister's conviction that it has to be Christianity doing the job, no other religion being apt to it, and his interpretation of proper Christianity at that, makes the impression of intolerance pungent. In 1944, this narrow perspective might have been somewhat understandable, but the English translation was published – under his supervision — in 1948, when the dreadful consequences of intolerance were obvious to everyone. What made him blind to this insensitivity was probably his conviction that his message dealt with the sacred, a divine perspective far above the turmoil of secular events. Conviction is known to cause loss of clear sight, and religious conviction is definitely no exception. Much like his previous texts discussed above, Christianity and Fear incorporates psychoanalytical theories and methods, but its perspective is mainly theological. This is a man of the cloth trying his best to keep his religion relevant in a changing world, using novel theories of psychology to make his case. His major shortcoming is that he demands of his findings to propagate his own faith, which takes its toll on his reasoning. Freud could have told him, and probably did as best he could in their correspondence, that religion and psychoanalysis are no perfect match. Already the fundamental principle of the Oedipus complex should have told him that. It presents religion as a consequence of guilt feelings, not at all a solution to them.

Notes

Freudians on Myth and Religion

This text is an excerpt from my book Psychoanalysis of Mythology: Freudian Theories on Myth and Religion Examined, from 2022. The excerpt was published on this website in February, 2026.

MYTH

IntroductionCreation Myths: Emergence and MeaningsPsychoanalysis of Myth: Freud and JungJungian Theories on Myth and ReligionFreudian Theories on Myth and ReligionArchetypes of Mythology - the bookPsychoanalysis of Mythology - the bookIdeas and LearningCosmos of the AncientsLife Energy EncyclopediaOn my Creation Myths website:

Creation Myths Around the WorldThe Logics of MythTheories through History about Myth and FableGenesis 1: The First Creation of the BibleEnuma Elish, Babylonian CreationThe Paradox of Creation: Rig Veda 10:129Xingu CreationArchetypes in MythAbout CookiesMy Other WebsitesCREATION MYTHSMyths in general and myths of creation in particular.

TAOISMThe wisdom of Taoism and the Tao Te Ching, its ancient source.

LIFE ENERGYAn encyclopedia of life energy concepts around the world.

QI ENERGY EXERCISESQi (also spelled chi or ki) explained, with exercises to increase it.

I CHINGThe ancient Chinese system of divination and free online reading.

TAROTTarot card meanings in divination and a free online spread.

ASTROLOGYThe complete horoscope chart and how to read it.

MY AMAZON PAGE

MY YOUTUBE AIKIDO

MY YOUTUBE ART

MY FACEBOOK

MY INSTAGRAM

STENUDD PĹ SVENSKA

|

Archetypes of Mythology

Archetypes of Mythology Psychoanalysis of Mythology

Psychoanalysis of Mythology