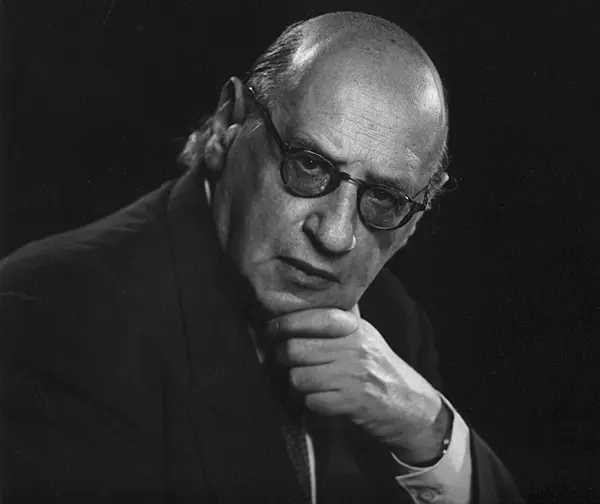

Theodor Reik

His theories about mythology and religion examined by Stefan Stenudd

In 1928 he moved to Berlin and set up a practice, but as Nazism rose, he moved to the Netherlands and in 1938 to New York, where he established a clinic and remained for the rest of his life. His writing on mythology is limited. Discussed below is a book on ritual, Ritual: Psycho-Analytic Studies, which was the first in what was supposed to be a series of books on problems in the psychology of religion, but no additional volumes were released. The volume on ritual was originally published in 1919, with a preface by Freud, and a revised second edition came in 1928. The English translation from 1931 is based on the second edition.

Psychoanalytic Studies of RitualThe book is a collection of four lectures held between 1914 and 1919 at the Berlin and Vienna branches of the International Psycho-Analytical Association. The four rituals discussed in the lectures are couvade, puberty rites, and the Jewish rites involving Kol Nidre and the Shofar. Since myths are only indirectly discussed, the treatment of his book will be limited to the first two rituals.Still, they do present some psychoanalytical perspectives on religion and mythology. Reik is not modest about what the discipline can reveal simply by exposing "those unconscious impulses, to which analysis points as determining the genesis and essence of religion."[1] That would not leave much undone. Regarding myth, Reik states firmly that it is older than religion, and "one of the oldest wish-compensations of mankind in its eternal struggle with external and internal forces."[2] Therefore, myth is "of the highest importance for our understanding of the first psychological conflicts of primitive people." Although it precedes religion, it allies itself with religious cults, sharing their history:

The events leading to the formation of religion he speaks of are those suggested by Freud as the prehistoric causes of the Oedipus complex. As stated both by him and in Freud's preface, Reik applies his teacher's Totem and Taboo to the analysis of rituals, and quite slavishly at that.[4] Reik's praise of the book is monumental. He describes it as "hitherto the most important work of the kind, and one that will always remain the standard illustration of what psycho-analysis can perform in the sphere of mental science." Although stressing the importance and antiquity of myth, Reik finds ritual particularly suitable for psychoanalytical approach, since it is an active expression of religion:

The more difficult question is to what extent they were firm beliefs to begin with. Some rituals may have been consciously composed fantasy projects from the start, with or without a belief backing them up. For example, the modern way of celebrating Christmas would be misunderstood if future researchers regarded it as proof of our belief in Santa Claus.

CouvadeCouvade is the term for the tradition in some cultures of the father restricting his behavior during and after the mother gives birth to their child. Although the term existed beforehand, E. B. Tylor introduced it to anthropology in 1865.[7] He translates it as "hatching." While the mother is in labor or approaching it or right after it, the father stays passive in bed as if the labor was his. In some cases, he also has dietary restrictions and is forbidden certain forceful activities, such as hunting big animals.A modern use of the term is couvade syndrome, which is the sympathetic pregnancy experienced by some fathers. But in his lecture on the subject from 1914, Couvade and the Psychogenesis of the Fear of Retaliation, Reik refers to the old ritual. Tylor and others explained the custom as an example of sympathetic magic, aimed at protecting the baby and easing the ordeal of the mother. Reik, in his psychoanalytical explanation, actually reverses it. He sees the father's behavior as based on the hidden unconscious wish to increase the mother's pain and even to kill the baby.[8] The father struggles unconsciously with these wishes, resulting in him masochistically striking himself with them, punishing himself with the pains. Thereby, his tender impulses have won over the hostile ones:

It is the dietary couvade that reveals repressed hostile impulses towards the child.[13] Again Reik uses a reversal. The restrictions on food and activity were supposed to be sympathetic magic for the protection of the child, and ignoring them might harm it, but: "The feared consequence of doing the forbidden things — the child would become sick and die — was once the desired consequence of the breaking out of hostile impulses."[14] Behind it all is the father's death wish towards the child. Reik makes a quick and frightful sketch of the mentality of the primitive human able to host such thoughts:

If that has any truth at all, it is certainly not "peoples" but individuals all on their own. Even in mythology it is depicted as a disgusting deed by deities soon suffering the punishment. Cronus (Saturn) is a famous example. And Jonathan Swift's A Modest Proposal from 1729 is, of course, nothing but a satire. Reik has an explanation to the father's vile hostility towards the child, which is at least equally far-fetched, though quite familiar to Freudian psychoanalysis. It is the Oedipus complex again. The primeval revolt against the father, relived in the minds of every following generation, ends up with the son becoming a father: "The son, who in childhood had wished the death of the father in order to take his place with the mother, has now himself become a man and father."[16] That means he would fear his son repeating the deed with him, but Reik insists on another complication: "In the belief of the savage people the child represents not the rebirth of its father, but the rebirth of its father's father."[17] No doubt, that increases the fear of retaliation. His son is none other than his own father, whom he revolted against.

Fathers killing their children are not unheard of in human history and in the present, but that does not mean it has ever been a strong urge in men. If so, it would have put a quick end to the procreation of our species. Even more absurd is the claim that rituals were needed to hinder fathers from eating their offspring. Reik is led astray by what he wants to find, whatever detours it makes him take. That is a streak he shares with his psychoanalytical colleagues. Already in choosing his subject he has obviously been attracted by the components of the Oedipus complex — the father, the mother, and the son. His commitment to Freud's doctrine and Totem and Taboo did the rest. Reik's prejudiced account of the ritual and how it was played out in different cultures makes it difficult to get enough of a clear picture of it to suggest other explanations. But Tylor and others have already suggested sympathetic magic, and that would lend itself to a less complicated explanation. Then the father lying in bed would really be an act of trying to ease the pain of the mother by accepting it to transfer into him during her labor, and maybe an act of transferring his power to her when he remained in bed after she had left it. Dietary restrictions would be due to the belief that father and child were connected and some food was regarded as harmful to the newborn, so the father avoided it to spare the child. This was also implied in some of the sources Reik used, though he brushed it aside. An interesting aspect is the need for passivity of the father, disallowing him to handle weapons or chasing big game, and so on. That would be taken care of by him remaining in bed, so it must belong to other versions of the couvade. Invoking personal powers as well as challenging fierce beasts would, if father and child were connected, intimidate and frighten the latter. There is also a possibility of the simple consideration that the father should not hurry to take risks when he had a newborn to protect.

Infanticide versus the Oedipus ComplexThere is no denying that fathers, like any male adults, have been more of a threat to infants than the mothers. History has proven it often enough, among both humans and many other animals. It would worry both a mother and an infant if the father started swinging a sword right after delivery.Still, it is doubtful that a brutal father would settle for a ritual doing the opposite of his intention. He might instead feel better raging after big prey. If other primates are comparable to humans in this context, infanticide is known among 35 of those species. They are not exclusively done by males or targeted at male infants, nor are they necessarily done in order to diminish competition for reproduction, but such cases do exist.[21] What is particularly rare among primates, though, is paternal and maternal infanticide. Humans may be the primates most inclined to infanticide of their own offspring, but it is definitely not a common occurrence. Not enough, really, for a complicated ritual to be formed and continued for multiple generations. What would make more sense, for humans as well as other primates, is a ritual to protect the newborn from other adults — male and female — than the parents. But that would be out of the scope of Freudian doctrine, which is based on the Oedipus complex. There are some intriguing similarities between male infanticide among mammals and the Oedipus complex. They involve a mortal drama between male, female, and child, with sexuality at the root. Males do it mostly to get access to impregnate the female. This is strongly supported by the fact that the behavior is not found among mammals with seasonal reproduction.[22] Only in species where the female can give birth the year around would the strategy make any sense, since it would speed up the possibility of impregnating her. It should be noted, though, that the males avoid killing their own offspring. Although it is not a behavior involving father and son, it is one where males compete ferociously about access to the females for sexual purposes. This makes Reik's insistence on the Oedipus complex even more far-fetched. It has nothing to do with patricide or the father's father, but with removing another male's child to gain access to the mother — in order for the aggressor to produce his own children with her. That is among many primates the real threat, maybe also in a distant past among humans. Psychoanalysts have focused on the son's envy of his father and the wish to take his place, already from infancy. What seems more plausible is the fear of the father. Paternal infanticide may be very rare, but the father's dominance and superior strength are not. The child's fate is helplessly in the hands of the father, not only in distant history. Children have good reason to regard their fathers as threats. Gender roles were quite clear in the society of Freud and his pupils. The father was the master, also the punisher, especially when the punishment was to be physical. A stern father would certainly by time cause vindictive longings in his son, but that would grow out of the torment of living in fear of him. The mother had little to do with it, except in cases of the son's frustration over her inability to protect him from the father. Nevertheless, there is reason to contemplate the tense relation between adult and infant males in both past and present societies, and the sexual implications of them. There is just no overwhelming support for describing it all with the theory of the Oedipus complex. Other explanations are nearer at hand.

Oedipal Puberty RitesIn 1915, at the Vienna Psycho-Analytical Society, Theodor Reik gave a lecture on a similar theme to the above: The Puberty Rites of Savages: Some Parallels between the Mental Life of Savages and of Neurotics. Again, he used Freud's Totem and Taboo to find the Oedipus complex at work in rituals, this time the rites of passage at puberty.With the term savages, he refers to hunter-gatherer societies, using an abundance of ethnological material from James G. Frazer and others. He does not deny that those societies have evolved through time, but he regards them as primitive in comparison to the ones of the industrialized parts of the world. As for the comparison to neurotics, he does it scarcely and superfluously. The bulk of his arguments are based on ethnographic material about the so-called primitives. There are two puberty rites his text focuses on — the circumcision and the ostensible death and resurrection of boys. He explains them, of course, as expressions of the Oedipus complex. They are to discourage the adolescents from killing their fathers and lusting after their mothers. The circumcision is a symbol of castration, intended to lessen the sexual drive of the boys, so that they will be able to resist their desires for their mothers, since "circumcision represents a castration equivalent and supports in the most effective way the prohibition against incest."[23] The ordeal of the ritualized death, which involves an imaginary monster Reik claims to represent the grandfather,[24] is the way of the fathers to scare the boys from trying to harm them:

He also takes a shot at Carl G. Jung for having presented an alternative to the Oedipus complex in his 1912 book Wandlungen und Symbole der Libido (published in English in 1916 as Psychology of the Unconscious), where the childish urge is instead described as an unconscious wish to return to the safety of the mother's womb and then to be reborn from it. To Reik, this is pure nonsense:

He accepts neither the opinions of the anthropologists whose material he is using, nor the answers given by the people whose rituals are described. He dismisses the reason for circumcision given by anthropologists and "primitives" alike, "that it is an operation for facilitating sexual intercourse and increasing its pleasures."[29] The real functions of the rites are unconscious and therefore hidden from the conscious minds of their practitioners:

A Rite of PassageIn his Freudian conviction, Reik refused to even consider other likely explanations, although they were accessible in the material he had at his disposal. He would have done well to start by putting this rite in relation to the other rites of passage[31] that are prominent and comparable in any society — past and present.There are four major passages or transformations humans go through in a lifetime: birth, puberty, procreation, and death. Each has a significant rite connected to it. In the Christian society they are the baptism, the confirmation, the wedding, and the funeral. There is little chance of understanding the emergence and components of one of these rites without seeing its relation to the other three. Obviously, the key is in the word "passage" used in anthropology for these rites. They are performed when life changes significantly from one situation to another, intended to prepare for as well as celebrate these changes. Newborns are baptized to be introduced into the community and receive their protection, and at the other end the dead are celebrated for their contribution and prepared for whatever is believed to come next. The wedding is an invitation for the couple to procreate, and to discourage others from pursuing them for the same purpose. The confirmation is a call to leave childhood and enter the world of the adults. Puberty is certainly a drastic change, physically as well as psychologically, in no need of the Oedipus complex to deserve a rite. Also, the components of the rite as described by Reik are easy to connect to the passage in question. The coming-of-age passage rite has the function of letting both the boy and his community know that now he has become a man. His childhood is over. That is a death and a rebirth — the child dies and the man is born. It also means that he detaches from his mother to make close bonds with the other men, which Reik instead explains as a measure to the prevention of incest.[32] This sheds light on the occurrence in the ritual of the boy behaving as if completely forgetful of his past when returning from the ordeal, which Reik described as peculiar: "The youths behave as though they had forgotten their previous life."[33] It is part of the transformation. The life of the child is to be forgotten, because there is a new life to live. Reik's explanation to this momentary amnesia is as elaborate as it is predictable:

Its role as an ingredient in a rite of passage is indicated also by the Jewish practice of performing circumcision soon after birth, which is of course another most significant passage. Although a Jew himself, Reik does not discuss that timing of the procedure in his text. It would put his oedipal explanation into question, since newborns are no threats to their fathers, nor are they likely to remember the lesson until puberty. There is something more with the circumcision, worthy of considering. It is the bleeding and its correspondence to the bleeding that signals the sexual maturity of girls. So, both sexes are introduced to their adult lives by the same bodily fluid, which is a vital and highly symbolic one, also in this case coming from their respective reproductive organs. Reik makes no mention of female puberty rites and he might not even have asked himself if they exist at all among natives. That would complicate matters for his understanding of the male rite and even of the Oedipus complex as a whole. Freud denied that it had a female counterpart, suggested by Jung as the Electra complex. The loyal Reik would not question Freud's view. On the other hand, he was hardly ignorant of the fact that in Western society, all four rites of passage mentioned are done for both genders. He had an excuse in the case of rites within hunter-gatherer societies, since the ethnographic material at the time was very scarce indeed with reports on female rites — simply because the field research was done by men. They would not have access to female rites, nor were they probably aware of their existence. Reik could have surmised the hidden existence of a female counterpart to the male rites, since he was aware of women being strictly excluded from the latter.[35] He also gives other examples of the male world that women were forbidden to enter. The guess that the same would be true for the opposite is not far off. Instead, Reik mentions the male secret societies spread among the "primitive" peoples of the world, as reported by the 19th century German ethnologist Heinrich Schurtz:

Of course, there are and have been many examples of female puberty rites around the world, often excluding men completely from participating. The first menstruation, menarche, is a passage of great significance in any culture, as it is to any girl.

Notes

Freudians on Myth and Religion

This text is an excerpt from my book Psychoanalysis of Mythology: Freudian Theories on Myth and Religion Examined, from 2022. The excerpt was published on this website in February, 2026.

MYTH

IntroductionCreation Myths: Emergence and MeaningsPsychoanalysis of Myth: Freud and JungJungian Theories on Myth and ReligionFreudian Theories on Myth and ReligionArchetypes of Mythology - the bookPsychoanalysis of Mythology - the bookIdeas and LearningCosmos of the AncientsLife Energy EncyclopediaOn my Creation Myths website:

Creation Myths Around the WorldThe Logics of MythTheories through History about Myth and FableGenesis 1: The First Creation of the BibleEnuma Elish, Babylonian CreationThe Paradox of Creation: Rig Veda 10:129Xingu CreationArchetypes in MythAbout CookiesMy Other WebsitesCREATION MYTHSMyths in general and myths of creation in particular.

TAOISMThe wisdom of Taoism and the Tao Te Ching, its ancient source.

LIFE ENERGYAn encyclopedia of life energy concepts around the world.

QI ENERGY EXERCISESQi (also spelled chi or ki) explained, with exercises to increase it.

I CHINGThe ancient Chinese system of divination and free online reading.

TAROTTarot card meanings in divination and a free online spread.

ASTROLOGYThe complete horoscope chart and how to read it.

MY AMAZON PAGE

MY YOUTUBE AIKIDO

MY YOUTUBE ART

MY FACEBOOK

MY INSTAGRAM

STENUDD PĹ SVENSKA

|

Archetypes of Mythology

Archetypes of Mythology Psychoanalysis of Mythology

Psychoanalysis of Mythology