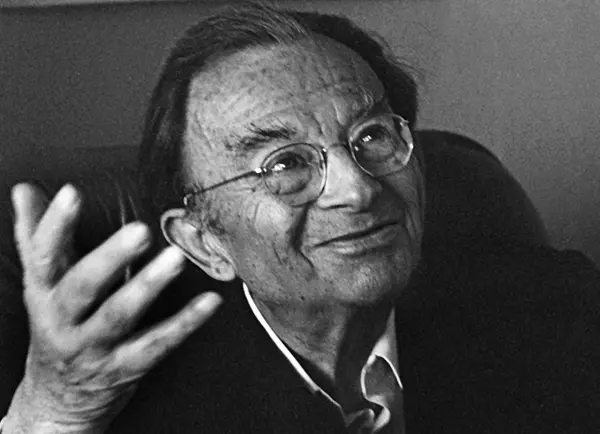

Erich Fromm:

|

by Stefan Stenudd |

It was meant to be part of a bigger project, but he decided to break his schedule to get this one out swiftly. His reason was the ongoing war and the dark forces instigating it. He wrote in the foreword:

Present political developments and the dangers which they imply for the greatest achievements of modern culture — individuality and uniqueness of personality — made me decide to interrupt the work on the larger study and concentrate on one aspect of it which is crucial for the cultural and social crisis of our day: the meaning of freedom for modern man.[1]

He was saddened and alarmed at this outbreak of totalitarianism: "We have been compelled to recognize that millions in Germany were as eager to surrender their freedom as their fathers were to fight for it."[2] But it was not only Germany and Italy. He saw signs of the same threat in other European nations. And he sought to explain it in terms of social psychology, which he believed was necessary in order to defeat the enemy: "For, the understanding of the reasons for the totalitarian flight from freedom is a premise for any action which aims at the victory over the totalitarian forces."[3]

By this time, he had admittedly moved far from his initially strict Freudian views, in particular regarding the importance of the social dynamics in society:

The viewpoint presented in this book differs from Freud's inasmuch as it emphatically disagrees with his interpretation of history as the result of psychological forces that in themselves are not socially conditioned.[4]

Fromm examines the emergence of human freedom from the boundaries of nature that surrounds him, as well as from just identifying with the collective of the human species. This realization was what truly initiated the development of human society:

The social history of man started with his emerging from a state of oneness with the natural world to an awareness of himself as an entity separate from surrounding nature and men.[5]

Interestingly, this process of the individual separation from the surrounding world Fromm calls individuation, a term otherwise made famous by Jung. While to Jung it is an introspective discovery, Fromm sees it as basically extrovert. It is man finding his identity different from nature, at first, and then also from fellow men. Fromm regards it as having reached its peak in the centuries between the Reformation and the present.

As a representation of this process and its complications, he turns to the biblical myth of the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden. He has a fresh and radical take on the meaning of the story, quite different from the biblical one:

The myth identifies the beginning of human history with an act of choice, but it puts all emphasis on the sinfulness of this first act of freedom and the suffering resulting from it.[6]

When Adam and Eve take their bites of the forbidden fruit they may commit a sin in the eyes of God, but they do suddenly break free of the spell of Eden and make up their own minds. They become separate from both God and the rest of his creation. In doing so, they achieve knowledge of good and bad, no less.

Thereby, they take the first step towards the ability to make up their own minds: "The act of disobedience as an act of freedom is the beginning of reason."

To Fromm, this first act of freedom is the first human act. Man has become separate from nature and has thereby taken the first step towards becoming an individual.

He acts against God's command, he breaks through the state of harmony with nature of which he is a part without transcending it. From the standpoint of the church which represented authority, this is essentially sin. From the standpoint of man, however, this is the beginning of human freedom.

This is far from an ideal state, though. By breaking free, man has also lost something: "He is alone and free, yet powerless and afraid." There was security in the care of God and life in Eden, and there was carelessness in ignorance.

Fromm describes it as the crucial difference between "freedom from" and "freedom to."[7] The former happens when the bonds are broken, but then the latter is needed — a meaningful active entrance into freedom and all that it can bring of continued individuation, of finding one's own life. There is sweetness in the revelation of one's individuality, and once it has happened there is no turning back.

Yet, there is a catch in this new perception of oneself in the world:

But on the other hand this growing individuation means growing isolation, insecurity, and thereby growing doubt concerning one's own role in the universe, the meaning of one's life, and with all that a growing feeling of one's own powerlessness and insignificance as an individual.[8]

Fromm sees only one possible solution for how the individualized man should relate to this brand-new world. It is by "his active solidarity with all men and his spontaneous activity, love and work, which unite him again with the world, not by primary ties but as a free and independent individual."

For this to work, the social situation must allow it and make it possible. Society must be so structured that it encourages this process. If not — if the economic, social, and political conditions do not make it possible — freedom becomes an unbearable burden.

This is the sad case, Fromm concludes. The consequence is that although the full emergence of the individual has gone on since the Renaissance and seems to have come to a climax, "the lag between 'freedom from' and 'freedom to' has grown too."[9]

Judgment Is Reciprocal

Fromm uses this biblical tale to illustrate what he sees as a principal development in the psyche of humankind, which is the realization of an 'I' distinctive from everyone and everything else in the world. As it happened in the history of our evolution, similarly Fromm sees it happen in the growing infant.[10]He does not insist that his interpretation of the biblical myth is the one also mythologically applicable, or at all intended by its ancient author. He merely uses it for his argument.

But the expulsion from Eden has mythological significance and similar accounts are found in other creation stories. In quite a number of them, humankind is regarded by the deities as something of a nuisance. We have no problem understanding why. This species is a difficult one to master or please. We only need to look at how hard it is for us to live peacefully among ourselves. Gods would do right to be wary of us.

The fall of man is part of the Bible's second creation story, and creation stories have their own rationale. Their main object is to explain in their own way what led to the present situation for humankind and the world — the present of the time of their composing, that is. They sort of filled in the blanks of human knowledge and understanding, and those were numerous in ancient times.

Accordingly, this particular biblical creation myth gives an account of why humans are mortal, why childbirth is painful, why snakes have no legs, and so on.

The most interesting part of this myth is indeed what fruit the first humans ate[11] — that of the tree which gives knowledge of good and bad. It implies that before Adam and Eve learned this, they were really neither good nor bad, since it would be impossible without knowledge of the concept. It really also makes them innocent of the crime of disobeying their god. They had no idea it would be bad.

It is an amusingly paradoxical situation, and God's reason for forbidding that fruit is not a noble one: It would make them more like him. He was already wary of his own creation, so he wanted to avoid the humans also eating of the tree of life, thereby becoming immortal like him. To stop that from happening, he had to expel them from Eden.

Still, it is food for thought that God would be so opposed to humans learning about good and bad, especially since he already in Eden expected them to act according to those principles. What was so dangerous about the ability to understand morality? And the first consequence of their enlightenment was to cover their nakedness. That is not much of a moral issue. It is little more than what we today would call a dress code. Yet, it was so important to God that he made sure to give Adam and Eve garments of skins before throwing them out of Eden.[12]

God's own moral standard, as it is presented in the Old Testament, can be questioned. It is hard to see that the expulsion of Adam and Eve was from a moral ground, whatever God claimed. It seems more like self-defense.

In any case, the punishment cannot be said to fit the crime — especially since it affected every following generation of humankind, though they were never near that fruit. God even admits to this basic principle of justice that only the one committing a crime can be punished for it. He states in Ezekiel that the son should not bear the iniquity of the father, nor the other way around.[13]

Maybe God's aversion to humans learning about good and bad was that then they might judge his actions. Job learned that God did not accept to be denounced or in any way have his actions measured by the creatures of his making.

It is safe to say that God was far from perfect, which is a trait he shared with numerous deities of other mythologies. Actually, it is hard to find even the suggestion of perfection among gods, especially outside monotheism. Christian theology has mostly insisted on it, though, but often from a philosophical standpoint — he would not be almighty if he were not perfect. The one is supposed to postulate the other.

In any case, Fromm's use of the myth makes sense as a symbolic account of humankind becoming a reasoning species. Good and bad might upon closer examination be very complicated concepts, indeed, but the ability to make a judgment, coming to a conclusion, is fundamental in reasoning.

To Fromm, though, the most important discovery separating modern man from his primeval ancestors is self-awareness — realizing that I am not you, nor anything else around me. But that is not as evident in the expulsion myth as is the awakening of reason. Eve even stated that she would eat of the fruit because she desired to become wise.[14] That suggests a preexisting self-awareness. And certainly, Adam and Eve had not been unaware of being separate from one another, as well as from God, the snake, and everything else in the Garden of Eden.

It might be proposed that Adam and Eve reached self-awareness when discovering each other's nudity. Indeed, the shame they showed fits with the emotional meaning of becoming self-aware as a moment of embarrassment caused by some flaw in one's behavior or features. But that is not much of a revelation.

There is one act of what can be called individuation of sorts taking place in Eden, right before the expulsion: Adam names his previously nameless wife Eve.[15] Although it is he who does it, and not she, it is still recognition of her own identity. Considering she was the one making them taste the fruit to receive its gift, she was worth it.

Notes

- Erich Fromm, Escape from Freedom (Die Furcht vor der Freiheit, 1941), New York 1976 (1st edition in English 1941), p. vii. ↑

- Ibid., p. 5. ↑

- Ibid., p. viii. ↑

- Ibid., p. 14. ↑

- Ibid., p. 24. ↑

- Ibid., pp. 33f. ↑

- Ibid., p. 35. ↑

- Ibid., p. 36. ↑

- Ibid., p. 37. ↑

- Ibid., pp. 30f. ↑

- The biblical text does not specify the fruit. In European depiction it has long been an apple, probably because of the Latin Versio Vulgata of the Bible, where apple and evil are spelled the same: malum. Several other fruits have been suggested in Jewish and Christian discourse. ↑

- Genesis 3:21. ↑

- Ezekiel 18:20. ↑

- Genesis 3:6. ↑

- Ibid., 3:20. ↑

Erich Fromm on Myth and Religion

Introduction

The Dogma of Christ

Escape from Freedom

Psychoanalysis and Religion

The Forgotten Language

You Shall Be as Gods

Shifting Perspectives

Freudians on Myth and Religion

Introduction

Sigmund Freud

Freudians

Karl Abraham

Otto Rank

Franz Riklin

Ernest Jones

Oskar Pfister

Theodor Reik

Géza Róheim

Helene Deutsch

Erich Fromm

Literature

This text is an excerpt from my book Psychoanalysis of Mythology: Freudian Theories on Myth and Religion Examined from 2022. The excerpt was published on this website in February, 2026.

MYTH

Introduction

Creation Myths: Emergence and Meanings

Psychoanalysis of Myth: Freud and Jung

Jungian Theories on Myth and Religion

Freudian Theories on Myth and Religion

Archetypes of Mythology - the book

Psychoanalysis of Mythology - the book

Ideas and Learning

Cosmos of the Ancients

Life Energy Encyclopedia

On my Creation Myths website:

Creation Myths Around the World

The Logics of Myth

Theories through History about Myth and Fable

Genesis 1: The First Creation of the Bible

Enuma Elish, Babylonian Creation

The Paradox of Creation: Rig Veda 10:129

Xingu Creation

Archetypes in Myth

About Cookies

My Other Websites

CREATION MYTHS

Myths in general and myths of creation in particular.

TAOISM

The wisdom of Taoism and the Tao Te Ching, its ancient source.

LIFE ENERGY

An encyclopedia of life energy concepts around the world.

QI ENERGY EXERCISES

Qi (also spelled chi or ki) explained, with exercises to increase it.

I CHING

The ancient Chinese system of divination and free online reading.

TAROT

Tarot card meanings in divination and a free online spread.

ASTROLOGY

The complete horoscope chart and how to read it.

MY AMAZON PAGE

MY YOUTUBE AIKIDO

MY YOUTUBE ART

MY FACEBOOK

MY INSTAGRAM

STENUDD PÅ SVENSKA

Stefan Stenudd

About me

I'm a Swedish author of fiction and non-fiction books in both English and Swedish. I'm also an artist, a historian of ideas, and a 7 dan Aikikai Shihan aikido instructor. Click the header to read my full bio.

Archetypes of Mythology

Archetypes of Mythology Psychoanalysis of Mythology

Psychoanalysis of Mythology