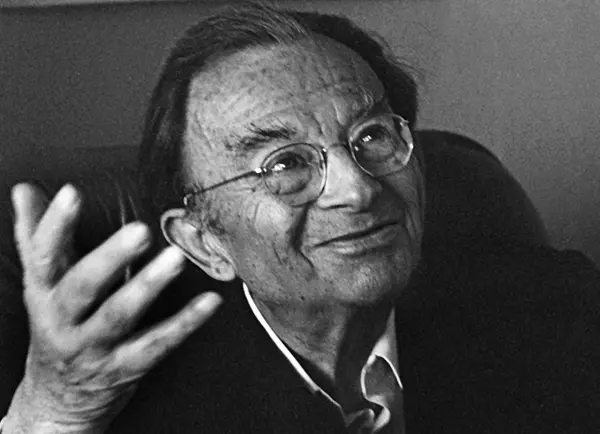

Erich Fromm: Psychoanalysis and Religion

Chapter 4 on his theories about mythology and religion examined by Stefan Stenudd

Fromm looked at this accelerating progress with ambiguity. A new horrific threat had appeared in that "scientists argue whether the atomic weapon will or will not lead to the destruction of the globe."[1] Although less dramatic, there was another threat to civilization, which may even have increased since then — the one of superficiality:

In the book, he gives no indication of other members of that third group than himself. He is not even clear about his own beliefs, but they seem not to include a deity:

Comparing the theories in those books, though, Fromm is quick to criticize Jung on several grounds, but not at all Freud. He opposes the understanding that Freud would be a foe of religion and Jung a friend of it. Instead, he concludes about their standpoints:

Jung stressed, like Fromm, the reality of religion in human minds regardless of the existence of any god. His idea of the collective unconscious, which must be what Fromm refers to, is definitely not one of divine character. He described it more like a highly developed inherited entity, comparable to the instincts although of much greater complexity. Jung was always vague about his own religious beliefs, but clear about them having no bearing on his theories. Fromm presents his own definition of religion: "I understand by religion any system of thought and action shared by a group which gives the individual a frame of orientation and an object of devotion."[10] This definition is both wide and vague. It would fit patriots of any nation, members of a political party, the fans of a rock group, and the supporters of a football team. Actually, it would fit just about any subculture. Both "frame of orientation" and "devotion" are insufficiently precise to have any meaning in a definition. Certainly, there is no fixed definition of religion on which scholars completely agree, but the component of the supernatural and the belief in laws other than those of nature ruling existence are usually included. One might say that religion has elements that are by their nature impossible to prove in the physical world, and therefore need to be a matter of faith. But that is exactly what Fromm wants to avoid. He argues for widening the concept of religion to practices and traditions without deities and other elements of pure faith, in order to incorporate ethical and philosophical teachings that would otherwise be hard to include. It becomes clear when he presents a division of religions into authoritarian and humanistic.[11] Authoritarian religion is the one with a church deciding the dogma and people are to submit to deities like sheep to the shepherd. Fromm finds an interesting correlation between the deity and humankind: "The more perfect God becomes, the more imperfect becomes man."[12] The elevated deity demands obedience and gives room for little else. Humans are supposed to lower their heads in shame afore the deity. In humanistic religion, people are free, even expected, to take care of their own spiritual development: "Man must develop his power of reason in order to understand himself, his relationship to his fellow men and his position in the universe."[13] Fromm uses the analogy of the fall and the flood of the Bible.[14] The former, where Adam and Eve are expelled from Eden for breaking God's command, is authoritarian. But in the story of the flood, Noah is working together with God to survive the flood, and after it there is the covenant between God and Noah, where both have obligations. That, to Fromm, is a sign of a humanistic religion. He finds humanistic religion in parts of otherwise authoritarian dogma, as well as way outside that territory:

Taoism, too, is more readily explained as a philosophy than as a religion. It might even be said about early Buddhism, and probably also for the Culte de la Raison of the French Revolution, which intended to replace Christianity with atheistic devotion towards the ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity. Fromm has widened the definition so much to incorporate this diversity, he might as well have gone the other way and found a concept in which to include religion. If so, the concept would not be philosophy, which is also wide and vague to say the least. But moral philosophy or ethics seem accurate for what Fromm discusses. The ideology of it stands out when he describes the true follower of humanistic religion, which is certainly what he advocates:

Without doing so, he risks falling into the trap of contributing to the "nonsense which would be offensive to the intelligence of children" he warns about. We all know that we should love one another, but even when we do so it often turns out much more complicated than what was foreseen. Love is no fix-all magic potion, and when it is, as in the story of Tristan and Iseult, it ends with disaster. Fromm must have some theory about the nature of love, since he states that "psychoanalysis also shows that love by its very nature cannot be restricted to one person."[20] He does not refer to self-love, but to loving just one other person. So, the love he speaks about might be compassion. While neglecting to define love with his psychoanalytical tools, Fromm applies them to the inspired sense of oneness that is a common religious experience, such as in the ecstasy of some devoted Catholics and the experience of satori in Zen meditation:

There are no archetypes in Fromm's unconscious. He does not mention the term in his book. But he does express a similar understanding of the symbols that appear in myths as well as dreams:

Close to JungReading Fromm, it is easy to come to the conclusion that his thoughts on psychoanalysis as well as his ethical agitation bring him much closer to Jung than to Freud. The same goes for his stance on religion and how psychoanalysis can approach it. His reluctance to compare Jung's ideas to his own may not stem so much from their differences as from a sense of competing on the very same arena.One crucial element of psychoanalytical theory, where he outspokenly agrees more with Jung than with Freud, is that of the Oedipus complex. To Freud it was definitely an expression of a longing for sexual incest at the root of the male psyche, but Jung found that interpretation far too narrow. He insisted that sexuality, though certainly important, is not that altogether dominant in the psyche and its complications. Often, he stated, it is a symbolic representation of something else. Fromm has the same objection, and he even gives Jung credit:

Furthermore, Fromm suggests that Freud really had a nuanced view on the subject: "Freud himself has indicated that he means something beyond the sexual realm." A source on this would have been fine. I have not seen any sign of it in the writing of Freud that I have gone through. Though Fromm praises Freud repeatedly and expresses ambivalence about Jung in his writing, the bulk of that writing shows more similarities to the latter than to the former. Fromm actually gives the impression of being a Jungian at heart, whatever he claims.

Notes

Erich Fromm on Myth and Religion

Freudians on Myth and Religion

This text is an excerpt from my book Psychoanalysis of Mythology: Freudian Theories on Myth and Religion Examined from 2022. The excerpt was published on this website in February, 2026.

MYTH

IntroductionCreation Myths: Emergence and MeaningsPsychoanalysis of Myth: Freud and JungJungian Theories on Myth and ReligionFreudian Theories on Myth and ReligionArchetypes of Mythology - the bookPsychoanalysis of Mythology - the bookIdeas and LearningCosmos of the AncientsLife Energy EncyclopediaOn my Creation Myths website:

Creation Myths Around the WorldThe Logics of MythTheories through History about Myth and FableGenesis 1: The First Creation of the BibleEnuma Elish, Babylonian CreationThe Paradox of Creation: Rig Veda 10:129Xingu CreationArchetypes in MythAbout CookiesMy Other WebsitesCREATION MYTHSMyths in general and myths of creation in particular.

TAOISMThe wisdom of Taoism and the Tao Te Ching, its ancient source.

LIFE ENERGYAn encyclopedia of life energy concepts around the world.

QI ENERGY EXERCISESQi (also spelled chi or ki) explained, with exercises to increase it.

I CHINGThe ancient Chinese system of divination and free online reading.

TAROTTarot card meanings in divination and a free online spread.

ASTROLOGYThe complete horoscope chart and how to read it.

MY AMAZON PAGE

MY YOUTUBE AIKIDO

MY YOUTUBE ART

MY FACEBOOK

MY INSTAGRAM

STENUDD PÅ SVENSKA

|

Archetypes of Mythology

Archetypes of Mythology Psychoanalysis of Mythology

Psychoanalysis of Mythology