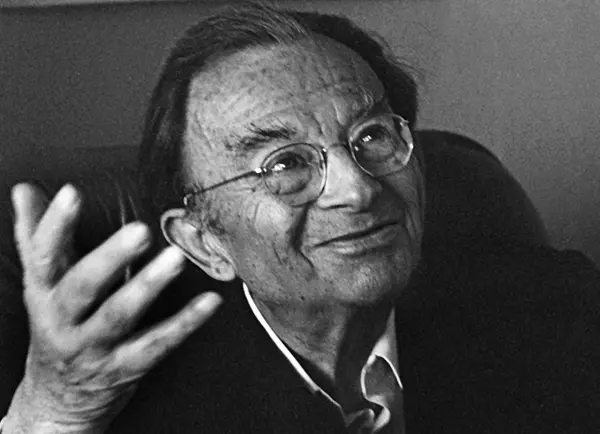

Erich Fromm:

|

by Stefan Stenudd |

Fromm claims not to be a theist[1] and calls his personal form of spirituality a nontheistic mysticism.[2] As for the deity, he states, "I believe that the concept of God was a historically conditioned expression of an inner experience." That does in no way stop him from holding the Old Testament in the highest regard:

The Old Testament is a revolutionary book; its theme is the liberation of man from the incestuous ties to blood and soil, from the submission to idols, from slavery, from powerful masters, to freedom for the individual, for the nation, and for all of mankind.[3]

It is with this view he spends the just under 200 pages of the book explaining what he regards as the proper way to interpret the Bible, which is that of radical humanism:

By radical humanism I refer to a global philosophy which emphasizes the oneness of the human race, the capacity of man to develop his own powers and to arrive at inner harmony and at the establishment of a peaceful world.[4]

It is quite an idealistic standpoint. He means that the god of the Old Testament promoted mankind's strife to achieve freedom — maybe even from the need of God.[5] Foremost in this struggle for freedom is discarding any kind of idol worship. To Fromm, idolatry is at the root of the unliberated and unrealized human being. It represents the object of man's central passion, "the desire to return to the soil-mother, the craving for possession, power, fame, and so forth."[6]

He also states:

The idol is the alienated form of man's experience of himself. In worshiping the idol, man worships himself.[7]

This is one of the few instances of a psychological perspective in the book. Another is when he sets out to define the so-called religious experience, which to him is the same whether theistic or nontheistic. Therefore, he relinquishes using the word religious for it, but calls it the x experience. He names five psychological aspects of it:

- The experience of life as a question requiring an answer,

- Setting the highest values for one's development,

- Transforming to become more human,

- Letting go of one's ego and fears,

- Leaving selfishness and learning to love life.[8]

It follows from all the foregoing considerations that the analysis of the x experience moves from the level of theology to that of psychology and, especially, psychoanalysis.[9]

That is because it calls for an understanding of unconscious processes underlying the x experience. But it has to go beyond Freud's outline of psychoanalysis, focused almost exclusively on the libido:

The central problem of man is not that of his libido; it is that of dichotomies inherent in his existence, his separateness, alienation, suffering, his fear of freedom, his wish for union, his capacity for hate and destruction, his capacity for love and union.[10]

Instead, Fromm suggests an empirical psychological anthropology, studying such experiences regardless of conceptualizations.

As for humankind's quest for freedom, its realization is the true meaning of a messianic time to come. It is the next step in history and not at all a doomsday: "The messianic time is the time when man will have been fully born."[11] At that point humans are liberated to act according to their finest potentials. Also the Sabbath, the day when things are left as they are, is a symbol of this:

The Sabbath is the expression of the central idea of Judaism: the idea of freedom; the idea of complete harmony between man and nature, man and man; the idea of the anticipation of the messianic time and of man's defeat of time, sadness, and death.[12]

Fromm's thoughts and sentiments are romantic, if not naïve, and his reasoning shows profound loyalty towards the Old Testament and the long Jewish tradition of its interpretation. It is all but completely within this scope that he goes to find support for his own interpretation. Therefore, it does not deviate significantly from that tradition.

His reverence sets him far apart from Freud's treatment of Moses as well as Jung's speculations based on the Book of Job. At no instance does he really question the wisdom of the Bible or its god, although he states that he does not regard it as the words of God, but "historical examination shows that it is a book written by men — different kinds of men, living in different times." Still, he persistently discusses it in a tone of dealing with something sacred and unquestionable.

Also, he insists on treating the whole of the Hebrew Bible as one book, although it has been compiled from many sources. His argument is that through its long history it has become one book.[13]

It is a pity that he makes this choice, since it ignores the many different contextual settings and their clues to inconsistencies as well as intentions. By relating to the Old Testament as both unquestionable and timeless, there is not much of an analysis left for Fromm to do.

Therefore, his conclusion is not different from that of its believers, which is that the biblical god is set on showing humankind the way to bliss, and if we just understand and follow his commands we will get there.

That can be questioned, but Fromm definitely does not. The good faith of this nontheist sometimes clogs his reasoning, when he explains the rationale of God's behavior. For example, when discussing the terribly fearsome side of the almighty, Fromm makes a distinction between threat and prediction, where the latter is creating awareness of the consequences instead of simply scaring people to change their ways. He asks the following rhetorical question, which does not help his case:

Does a father, telling his son that he will spank him if he does not do his homework, threaten him or is his threat an indirect expression of the prediction that he will fail in school (and in life) if he does not acquire self-discipline and a sense of responsibility?[14]

The simple answer is that yes, it is a threat and nothing else, whatever the intention. A prediction would be if the father warned him that he will get a failing grade if not doing his homework, but the punishment he threatens his son with has no direct relation to the consequences of the boy's studying efforts. It is a means of pressuring him to comply, in other words a threat.

The god of the Bible has indeed made the same kind of threats and on a much grander scale. People must obey or else, simply because he demands it. And the punishments he threatens with are usually monstrously out of proportion. No wonder the people of his creation, as well as the boy threatened with spanking, have great difficulty learning the lesson.

Fromm's reasoning in You Shall Be as Gods is similar, even repetitious, of his discussions in the above-mentioned books. It is clear that the psychologist in him has been drowned out by the ideologist. That may be commendable, but for the purpose of this book's topic it is disappointing. Although he writes extensively about religion, he contributes little to the psychoanalysis of mythology.

Notes

- Erich Fromm, You Shall Be as Gods: A Radical Interpretation of the Old Testament and Its Tradition, Greenwich 1966, p. 10. ↑

- Ibid., p. 18. ↑

- Ibid., pp. 9f. ↑

- Ibid., pp. 14f. ↑

- Ibid., p. 23. ↑

- Ibid., p. 36. ↑

- Ibid., p. 37. ↑

- Ibid., pp. 47ff. ↑

- Ibid., p. 49. ↑

- Ibid., p. 50. ↑

- Ibid., p. 98. ↑

- Ibid., p. 153. ↑

- Ibid., pp. 10f. ↑

- Ibid., p. 139. ↑

Erich Fromm on Myth and Religion

Introduction

The Dogma of Christ

Escape from Freedom

Psychoanalysis and Religion

The Forgotten Language

You Shall Be as Gods

Shifting Perspectives

Freudians on Myth and Religion

Introduction

Sigmund Freud

Freudians

Karl Abraham

Otto Rank

Franz Riklin

Ernest Jones

Oskar Pfister

Theodor Reik

Géza Róheim

Helene Deutsch

Erich Fromm

Literature

This text is an excerpt from my book Psychoanalysis of Mythology: Freudian Theories on Myth and Religion Examined from 2022. The excerpt was published on this website in February, 2026.

MYTH

Introduction

Creation Myths: Emergence and Meanings

Psychoanalysis of Myth: Freud and Jung

Jungian Theories on Myth and Religion

Freudian Theories on Myth and Religion

Archetypes of Mythology - the book

Psychoanalysis of Mythology - the book

Ideas and Learning

Cosmos of the Ancients

Life Energy Encyclopedia

On my Creation Myths website:

Creation Myths Around the World

The Logics of Myth

Theories through History about Myth and Fable

Genesis 1: The First Creation of the Bible

Enuma Elish, Babylonian Creation

The Paradox of Creation: Rig Veda 10:129

Xingu Creation

Archetypes in Myth

About Cookies

My Other Websites

CREATION MYTHS

Myths in general and myths of creation in particular.

TAOISM

The wisdom of Taoism and the Tao Te Ching, its ancient source.

LIFE ENERGY

An encyclopedia of life energy concepts around the world.

QI ENERGY EXERCISES

Qi (also spelled chi or ki) explained, with exercises to increase it.

I CHING

The ancient Chinese system of divination and free online reading.

TAROT

Tarot card meanings in divination and a free online spread.

ASTROLOGY

The complete horoscope chart and how to read it.

MY AMAZON PAGE

MY YOUTUBE AIKIDO

MY YOUTUBE ART

MY FACEBOOK

MY INSTAGRAM

STENUDD PÅ SVENSKA

Stefan Stenudd

About me

I'm a Swedish author of fiction and non-fiction books in both English and Swedish. I'm also an artist, a historian of ideas, and a 7 dan Aikikai Shihan aikido instructor. Click the header to read my full bio.

Archetypes of Mythology

Archetypes of Mythology Psychoanalysis of Mythology

Psychoanalysis of Mythology