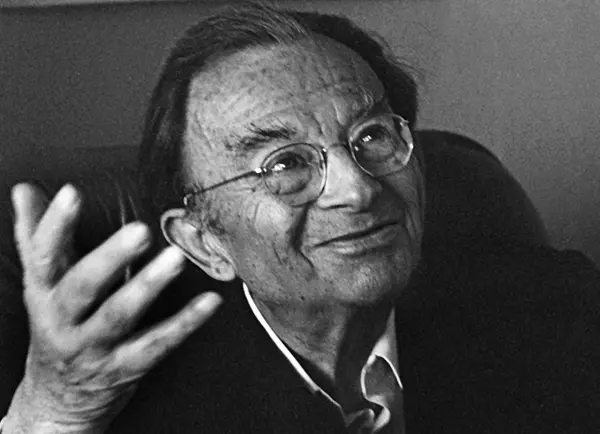

Erich Fromm:

|

by Stefan Stenudd |

Of course, he speaks of two separate religions — Christianity versus Judaism — but it still reveals radically different perspectives on religion. What he chose to pay attention to in 1930 was religion as a threat to the humanistic society he propagated, whereas in 1966 he points out how religion is a tool by which to reach that utopia.

In the former case, he needed to concentrate on how the dogma was interpreted and utilized by the rulers of society, but in the latter, he remains with theological speculations regardless of their use in society through history.

As for Christianity, he concludes that the original ideas of it were good, but they were corrupted when put to use in society. For Judaism, which has had far less influence on societies around the world, he just settles with the first part of the statement: the original ideas of it, as he interprets them, were good.

Judaism has never been put to the serious test that befell Christianity — the consequences of widespread success. Therefore, it is easy to claim Judaism's benefits, but not without the risk of turning it into an idol.

Considering Fromm's interest in social psychology and its dynamics, it is disappointing that he does not even try to speculate on what kind of corruption the Old Testament dogma as he understands it would risk if applied on a grander scale in society.

When he was 41 years old, Fromm released the book he may be most famous for: Escape from Freedom, discussed earlier. There he examined the Old Testament's account of the fall, when Adam and Eve bit the forbidden fruit and were expelled from the Garden of Eden. Seeing this as the first act of freedom, when man truly becomes man, he admitted that this was not the Bible's interpretation of the event. He used it as a symbolic starting point for his discussion about the need for humankind to become independent of a deity as well as of other authorities.

This was a very different take on the Bible from that of You Shall Be as Gods, 25 years later. In the previous book, he did not in any way claim that his interpretation of the Bible was identical to its original meaning or God's intention. On the contrary, he pointed out that he had his own twist on it.

God's worry and anger is just as evident in Fromm's text from 1941 as it is in Genesis. So is God's purpose. But in 1966 Fromm goes through all kinds of elaborate arguments to indicate that the Bible as well as its deity had a nobler intent than what meets the eye upon reading Genesis.

He points out that after creating man, God did not say that it was good, which he did with other creations of his. Thereby it was implied that man's creation was unfinished. God intended further development, which to Fromm can be nothing but the step towards freedom from the mother's womb of Paradise.[1] What might seem like an even more convincing argument is that the Bible never calls Adam's act a sin.[2] Well, it doesn't have to. God is quite clear about that in his response.

It is difficult to speculate on why Fromm would turn from the rebellious view towards the Bible when he was 41 to the apologist one when he was 66. It can't be as simple as the Swedish proverb states: "When the devil gets old, he gets religious."[3]

The transition of Fromm's thought and his reason for it may have been revealed already in the 1950 book Psychoanalysis and Religion, discussed earlier. In it, he complained about the materialism and superficiality he saw conquering society a few years after the end of Word War II. He argued for the religious perspective as a necessary antidote.

But he did so by altering the concept of religion to include spiritual doctrines and beliefs which do not contain any deities. Also, he made the distinction between authoritarian and humanistic religions, obviously propagating the latter. His use of the term religion was so odd that one has to wonder why he persisted with it. What he talked about is definitely closer to ethics, and his ideal could simply be described as compassion.

Still, his choice to reinterpret the principles of religion into accommodating his ideals, instead of finding another more fitting concept, would explain his development from exposing the flaws of the Bible into making it a companion, an ally, in 1966. Also in this respect, his development approached that of Carl G. Jung.

The Freudian Who Would Be a Jungian

The remaining conundrum with Erich Fromm is why he didn't become a Jungian. Though partially critical of Freud's theories, Fromm held him high all through his life.On the year of his death in 1980, Fromm's book Greatness and Limitations of Freud's Thought was published. Already in the first sentence of the preface, he speaks of "the extraordinary significance of Freud's psychoanalytic discoveries" and compares it to the words in John 8:32: "And the truth shall make you free."[4] That is praise in absurdum.

Jung is mentioned only five times, and not a single one of his many books is listed in the bibliography — although Fromm had definitely read several of them. His first mention of Jung is an interesting combination of praise and dismissal. Considering Freud's insistence on sexuality as the root of all drives, he writes:

It was Jung who later cut loose from this connection, and in this respect made, as I see it, a truly valuable addition to Freud's thought.[5]

Seeing Jung's standpoint as merely an addition to Freud's thought is both an insult and incorrect. Jung opposed Freud on this and other issues, unable to change Freud's mind. It was not a question of adding to Freud's theory, since he didn't allow any deviation from it. Fromm cannot have been unaware of this. He hid his disrespect for Jung inside a compliment.

That is particularly disappointing coming from a man so occupied in his writing with ethics. I see no other explanation than that he found Jung a competitor with theories much like his own. Maybe he was bitter about having followed Freud for so long, instead of turning his attention to Jung, whose thoughts definitely fitted his own speculations much better?

Notes

- Fromm, You Shall Be as Gods, p. 57. ↑

- Ibid., p. 125. ↑

- In Swedish, "När fan blir gammal blir han religiös." An old variation of it reads, "When the whore gets old, she gets godly." ("När horan blir gammal, blir hon gudfruktig.") Lars Rhodin, Samling af swenska ordspråk, Stockholm 1807, p. 101. ↑

- Erich Fromm, Greatness and Limitations of Freud's Thought, 1980, p. ix. ↑

- Ibid., pp. 5f. ↑

Erich Fromm on Myth and Religion

Introduction

The Dogma of Christ

Escape from Freedom

Psychoanalysis and Religion

The Forgotten Language

You Shall Be as Gods

Shifting Perspectives

Freudians on Myth and Religion

Introduction

Sigmund Freud

Freudians

Karl Abraham

Otto Rank

Franz Riklin

Ernest Jones

Oskar Pfister

Theodor Reik

Géza Róheim

Helene Deutsch

Erich Fromm

Literature

This text is an excerpt from my book Psychoanalysis of Mythology: Freudian Theories on Myth and Religion Examined from 2022. The excerpt was published on this website in February, 2026.

MYTH

Introduction

Creation Myths: Emergence and Meanings

Psychoanalysis of Myth: Freud and Jung

Jungian Theories on Myth and Religion

Freudian Theories on Myth and Religion

Archetypes of Mythology - the book

Psychoanalysis of Mythology - the book

Ideas and Learning

Cosmos of the Ancients

Life Energy Encyclopedia

On my Creation Myths website:

Creation Myths Around the World

The Logics of Myth

Theories through History about Myth and Fable

Genesis 1: The First Creation of the Bible

Enuma Elish, Babylonian Creation

The Paradox of Creation: Rig Veda 10:129

Xingu Creation

Archetypes in Myth

About Cookies

My Other Websites

CREATION MYTHS

Myths in general and myths of creation in particular.

TAOISM

The wisdom of Taoism and the Tao Te Ching, its ancient source.

LIFE ENERGY

An encyclopedia of life energy concepts around the world.

QI ENERGY EXERCISES

Qi (also spelled chi or ki) explained, with exercises to increase it.

I CHING

The ancient Chinese system of divination and free online reading.

TAROT

Tarot card meanings in divination and a free online spread.

ASTROLOGY

The complete horoscope chart and how to read it.

MY AMAZON PAGE

MY YOUTUBE AIKIDO

MY YOUTUBE ART

MY FACEBOOK

MY INSTAGRAM

STENUDD PÅ SVENSKA

Stefan Stenudd

About me

I'm a Swedish author of fiction and non-fiction books in both English and Swedish. I'm also an artist, a historian of ideas, and a 7 dan Aikikai Shihan aikido instructor. Click the header to read my full bio.

Archetypes of Mythology

Archetypes of Mythology Psychoanalysis of Mythology

Psychoanalysis of Mythology