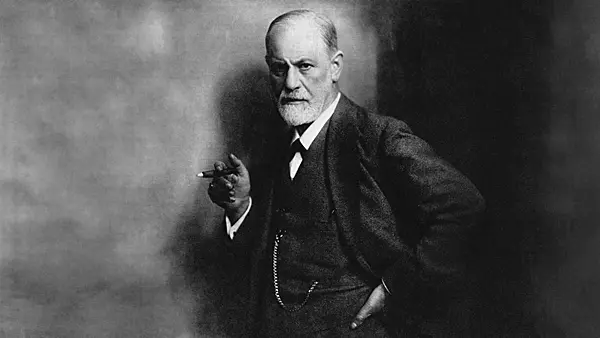

Sigmund Freud:

|

by Stefan Stenudd |

The first translation into English, by the psychiatrist Abraham Arden Brill who had also translated The Interpretation of Dreams, was published in 1918.

In the book, Freud refers to the pioneering psychologist Wilhelm Wundt (1832-1920) and Carl G. Jung as the first stimulus for his work on the subject.[1] In Jung's case he specifies the text Transformations and Symbols of the Libido, published in 1912.[2] However, Freud points out that his method "contrasts" both these sources. Wundt neglected to use analytic psychology, and Jung strove to "settle problems of individual psychology by referring to material of racial psychology."

Racial perspectives on psychology as well as on biology were, sadly, widely applied and respected in the scientific community of those days. So was the concept of the savage, which described people in hunter-gatherer societies and other cultures outside of modern industrial civilization as primitive remnants of earlier stages of human evolution.

Already the title Totem and Taboo indicates that this text relates to ritual more than to myth, searching for psychological explanations to certain traditions found in what Freud calls primitive society, as well as to some extent in his contemporary world. He compares taboo beliefs to neurosis, seeing both similarities and differences but expressing his belief in common psychological roots for them.

He also boldly claims to explain the origin of religion, ethics, society, and art. That's just about all of mankind's major endeavors.

Skeptical Reception

His text was met with some skepsis — and still is, to say the least. Already in a 1914 review of the book, Carl Furtmüller, a former member of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society, complained that Freud ignored critics, misused Darwin, and claimed the Oedipus complex to be the original sin of the human race. To Furtmüller, the book contained "the free play of fantasy."[3]The cultural anthropologist Alfred Louis Kroeber reviewed the book in 1920 with equally harsh words. Although agreeing that psychology had an important place in ethnology, he dismissed Freud's conclusion that the beginnings of religion, ethics, society, and art meet in the Oedipus complex.[4] He dismissed or questioned eleven of Freud's arguments and called his reasoning insidious.

To Kroeber, Freud's book "substitutes a plan of multiplying into one another, as it were, fractional certainties — that is, more or less remote possibilities — without recognition that the multiplicity of factors must successively decrease the probability of their product."

His judgment was firm: "Freud cannot be charged with more than a propagandist's zeal and perhaps haste of composition."[5]

An Original Patricide

Freud had his own radical explanation to the birth of religion, which has mostly met with rejection close to ridicule from historians of religion. Still, he remained convinced of his theory, which he also declared in Moses and Monotheism, published the same year he died.To his credit, he was already at the outset modest about the power of proof in his material. The fourth chapter of Totem and Taboo, where he presents his theory on the origin of religions, starts with the following obvious reservation, which passed unnoticed by some of his critics:

The reader need not fear that psychoanalysis, which first revealed the regular over-determination of psychic acts and formations, will be tempted to derive anything so complicated as religion from a single source.[6]

On the other hand, later on in that long chapter, he claims:

I want to state the conclusion that the beginnings of religion, ethics, society, and art meet in the Oedipus complex. This is in entire accord with the findings of psychoanalysis, namely, that the nucleus of all neuroses as far as our present knowledge of them goes is the Oedipus complex.[7]

Freud based his theory mainly on the psychoanalytical thesis of the Oedipus complex, and on totemism — to the point that he called this chapter of the book "The Infantile Recurrence of Totemism."

The term totemism was introduced in 1791 by John Long, who wrote about his experiences with Canadian natives.[8] At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, there was a wide-spread fascination among anthropologists about totemism.

The phenomenon that a family or a clan had a ritualized symbolic relation to a specific animal species, with which they claimed to be linked or even related, was known beforehand. But it received increased attention through the Scottish researcher John Ferguson McLennan, who in 1869 presented the idea that totemism might lie behind a number of customs, where totemism itself had disappeared.[9]

What attracted Freud's interest was first and foremost:

Almost everywhere the totem prevails there also exists the law that the members of the same totem are not allowed to enter into sexual relations with each other; that is, that they cannot marry each other. This represents the exogamy which is associated with the totem.[10]

One would think that the rule against sexual intercourse within the clan was intended as a protection against incest and inbreeding, but to this Freud objects that he doubts such civilized behavior among the "primitive" people. He also claims, without presenting support for it, that the damaging effects of inbreeding are not ascertained. He strongly rejects the possibility of such awareness among the primitives of the past:

It sounds almost ridiculous to attribute hygienic and eugenic motives such as have hardly yet found consideration in our culture, to these children of the race who lived without thought of the morrow.[11]

In a footnote to this statement, he takes support in Charles Darwin, quoting him about savages: "They are not likely to reflect on distant evils to their progeny." It is from the second edition of Darwin's The Variation of Animals and Plant under Domestication, but that wording is missing from the first edition. Darwin dismissed some contemporary theories about the reasons for prohibitions against marriages between kin:

But I cannot accept these views, seeing that incest is held in abhorrence by savages such as those of Australia and South America, who have no property to bequeath, or fine moral feelings to confuse, and who are not likely to reflect on distant evils to their progeny.[12]

So, Freud shared with Darwin the conviction that societies seemingly simpler than their own were populated by simple minds, unable to observe what the consequences of inbreeding could be. They gave no sign of putting that thesis to the test.

In Totem and Taboo, Freud connects totemism's sexual restrictions to the Oedipus complex. He sees the totem as an image of a forefather, who had expelled his sons from the "horde" he ruled, to prevent them from having intercourse with the women of the horde. The sons would not have that: "One day the expelled brothers joined forces, slew and ate the father, and thus put an end to the father horde."[13]

As additional indication of this, Freud mentions the ritual meals documented in totemism, where the totem animal might get served. In a footnote to this passage, he refers to known similar behavior among some flock animals, also he claims support from Charles Darwin and from the anthropologist James Jasper Atkinson.

The latter's 1903 book Primal Law is quoted:

A youthful band of brothers living together in forced celibacy, or at most in polyandrous relation with some single female captive. A horde as yet weak in their impubescence they are, but they would, when strength was gained with time, inevitably wrench by combined attacks renewed again and again, both wife and life from the paternal tyrant.[14]

Freud refers to Charles Darwin about his theories on the primal social state of man:

From the habits of the higher apes Darwin concluded that man, too, lived originally in small hordes in which the jealousy of the oldest and strongest male prevented sexual promiscuity.[15]

Freud definitely thinks that the patricide had taken place in a distant past, but admits that he may have comprised the development of events, and ends an extensive footnote:

It would be just as meaningless to strive for exactness in this material as it would be unfair to demand certainty here.[16]

Freud moves on to claim that the guilt of the sons, and a wish for some kind of reconciliation, made them start to worship their dead father like a god, in the form of a totem, and to restrain their sexual habits by exogamy, seeking their mates outside the herd. This was also necessary for them in order to keep their group loyalty and avoid competing to repeat the behavior of their father:

Thus there was nothing left for the brothers, if they wanted to live together, but to erect the incest prohibition — perhaps after many difficult experiences — through which they all equally renounced the women whom they desired, and on account of whom they had removed the father in the first place. [17]

He goes on to suggest that the bond between these men was one formed during their banishment, probably deepened by homosexual tendencies while they were deprived of female companions. In the guilt-triggered glorification of the father, Freud sees the insoluble tension that nourishes religion:

All later religions prove to be attempts to solve the same problem, varying only in accordance with the stage of culture in which they are attempted and according to the paths which they take; they are all, however, reactions aiming at the same great event with which culture began and which ever since has not let mankind come to rest.[18]

Somewhat triumphantly, Freud ends his book by stating: "In the beginning was the deed."[19]

A Male World

Freud's theory describes a very male world, indeed. The women are but objects of desire, completely passive and insignificant in any other way. If he at all admits them to wrestle with their own problems of the soul — and there is no mention of it in Totem and Taboo — the women have no active role at all in the formation of religion. One wonders why they would care to participate in the worship of that father figure.Freud was far from alone neglecting female influence in society, at the time he wrote his book as well as long before and after it. Indeed, society at his time was ruled almost exclusively by men. But there were exceptions.

He wrote his text little more than a decade after the death of Queen Victoria in 1901. She was a very prominent figure all over the world during her long reign. That was when Great Britain was by far the most powerful of countries, its rule reaching so far that the sun was rightly said never to set on the empire.

Women had made their marks in other fields as well. The Nobel Prize shows evidence of it. Marie Curie got it in physics 1903 and then again in chemistry 1911. Selma Lagerlöf got it in literature 1909, and she was far from the only female writer read and admired by millions. Bertha von Suttner was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1905. The list of prominent women at the time Freud wrote his book can be made quite long, but suffice to say that he cannot have been unaware of female influence in society, also in fields where men dominated overwhelmingly.

Even more alarming in his case is that he studied the human psyche and its manifestations. How to do that while excluding the influence of half of humankind?

If men were driven in their actions by competing over the women, how could the behavior of the objects of their desire be neglectable? There could be no Oedipus complex without women.

It is hard to comprehend how Freud could spend so much of his intellectual effort on the theory of the Oedipus complex without considering — or even discussing — the importance of the woman's role in this drama.

Carl G. Jung did so, already in 1912. He introduced the female counterpart to the Oedipus complex, calling it the Electra complex after the princess in Greek mythology, who plotted to have her mother killed:

In the case of the son, the conflict develops in a more masculine and therefore more typical form, whilst in the daughter, the typical affection for the father develops, with a correspondingly jealous attitude toward the mother. We call this complex, the Electra-complex.[20]

But Freud rejected the term. In a footnote to a 1920 essay on female homosexuality he states: "I do not see any progress or advantage in the introduction of the term 'Electra-complex,' and do not advocate its use."[21] He strongly denied the possibility of a female counterpart to the Oedipus complex. In his essay Female Sexuality from 1931 he writes:

We have the impression that what we have said about that complex applies in all strictness only to male children, and that we are right in rejecting the term "Electra complex" which seeks to insist that the situation of the two sexes is analogous. It is only in male children that there occurs the fateful simultaneous conjunction of love for the one parent and hatred of the other as rival.[22]

The firmness of Freud's prejudiced statement is equaled by the folly of its claim. In this particular context, what stands out is the crack it makes in his theory. The greater he proposes the impact of the Oedipus complex to be on society and its inhabitants, the bigger the need gets to explain the absence of half of them in his model.

The genders interact. Women act upon what men do, and vice versa. So did Jocasta in the Sophocles drama, when finding out that her spouse Oedipus was also her son. And in Lysistrata, the Aristophanes comedy from the same period, the women play the men as if they were puppies. What would not the women do if a patriarch expelled their brothers, sons, and lovers? One thing is for sure — they would not worship him, dead or alive.

History shows no sign of religion being an exclusively male undertaking. Worship has been as devout from both sexes. Therefore, it must have other sources than one that applies only to men.

Freud needed to make the women passive bystanders in order for his theory to compute. Otherwise, it would fail to explain that through the millennia, religion has attracted both sexes. He made religion an exclusively male thing.

Certainly, men have been in firm control of the higher offices of religion, especially in the three monotheisms. Paul expressed it in his first letter to the Corinthians:

Let your women keep silence in the churches: for it is not permitted unto them to speak; but they are commanded to be under obedience as also saith the law. And if they will learn any thing, let them ask their husbands at home: for it is a shame for women to speak in the church.[23]

Catholicism continues to use it as an excuse to refuse female priests. But in Protestantism, the exceptions are countless and the attitude another — as of lately. But never have women been forbidden to worship and partake in the rituals and celebrations of those religions.

Both sexes have always been expected to be faithful to their god. That god may be described as male, but he is still the god of both men and women.

The only way Freud's theory of the origin of religion could make sense, would be if women had been excluded from worship, and happily so. A purely male need for religion would hardly raise a need for it in women. That is definitely not what history has shown. Religion has proven to fill a need for men and women alike.

Irrelevant to Polytheism

Another striking omission in Freud's theory as presented in Totem and Taboo is that of polytheism. The sovereign primordial father god of the monotheisms is hard to find in polytheistic religions, which are most of them.Strictly speaking, only three religions are monotheistic — and they are closely related: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. The other ones are either clearly polytheistic or vague about gods as such.

Well, there is such a variety of religions and mythologies over the world and through the millennia, any simplified sorting of them is bound to have numerous exceptions. There are or have been other religions fitting the definition of monotheism just as well as the three Abrahamic ones. That can be said about Zoroastrianism, Sikhism, and Pharaoh Akhenaton's short-lived sun god worship mentioned by Freud in his book Moses and Monotheism.

Still, the monotheism Freud discusses, with a fatherly high-god who is the creator of the world and whose power is unmatched by any other, fits but few of the religions we know, compared to the vast number of polytheisms in the world now and in the past. Freud's model of an original patricide fails to explain polytheism, although for sure there are lots of patricides in their mythologies, even among the gods.

The oldest known example of this is from ancient Mesopotamian mythology, where the fresh water god Apsu, who is the mate of the salt water goddess Tiamat, is killed by his son Ea. The story is told in the Babylonian text Enuma Elish, composed in the 2nd millennium BC, but the Sumerian origin of the myth may be one or even two thousand years older. In spite of the patricide, the Sumerian and Babylonian mythologies are exceedingly polytheistic.

A classical example from Greek mythology of the battle between father and son, also with quite a Freudian ingredient, is Cronus castrating and overthrowing his father Uranus. The sickle he used was given to him by his mother Gaia, who encouraged the deed. Cronus, in turn, was gutted by his son Zeus, who had good reason for it. Thereby he released other children of Cronus who had been devoured by him.

Still, Greek religion cannot by any means be called monotheistic in the sense of worshipping only an elevated father figure. The Greek pantheon had a sovereign in Zeus, but he was far from the only one worshipped. Nor was there any overwhelming male dominance of gods, either in number or in feats.

With or without patricide, the polytheistic religions — and there are lots of them — remain anomalies to Freud's paradigm. He had no explanation to their emergence. That should have told him he might have been wrong about the emergence of monotheism, as well.

Alternative Explanations

Another thing lacking in Totem and Taboo is the exploration of what possible alternative explanations to the emergence of religion there might be, whether or not only in monotheism. Without at least trying other possibilities, if only to dismiss them, Freud could not have had much trust in his own hypothesis.Instead, Freud spent his text listing the examples and circumstances that might support his theory, at least not refute them. It is about as solid as picking a few black cats to prove that all cats are black. There are lots of cats. There are also lots of religions and lots of theories to explain their emergence.

Granted, at the time Freud wrote his book there were not as many theories about the origin of religion as there are now, but still they were not few. One of the oldest is that of the Greek statesman Critias, who was the uncle of Plato, living in the 5th century BC. His very blunt view on religion and its source was expressed in a satyr-play of his, Sisyphus, where the title role explains:

There was a time when the life of men was unordered, bestial and the slave of force, when there was no reward for the virtuous and no punishment for the wicked. Then, I think, men devised retributory laws, in order that Justice might be dictator and have arrogance as its slave, and if anyone sinned, he was punished. Then, when the laws forbade them to commit open crimes of violence, and they began to do them in secret, a wise and clever man invented fear (of the gods) for mortals, that there might be some means of frightening the wicked, even if they do anything or say or think it in secret. Hence, he introduced the Divine, saying that there is a God flourishing with immortal life, hearing and seeing with his mind, and thinking of everything and caring about these things, and having divine nature, who will hear everything said among mortals, and will be able to see all that is done.[24]

I must say that I find the old Critias claim much more convincing, already at first glance, than that of Freud. In its simplicity it also passes the test of Ockham's razor smoothly, by not needing a much-specified series of events and equally specified human reactions to them.

But Critias's theory about the birth of religions was far from the only one around, at the time Freud wrote his book. A little more than a century after Critias, Euhemerus suggested that the myths were enhanced accounts of ancient history, and the gods were kings and heroes of old. His theory was later to be repeated by others, to the point that this kind of explanation was given his name: euhemerism.

In the Christian era, speculating about the origin of religion being anything else than God's creation of man was blasphemous and could very well lead to the capital punishment. But that changed in the 19th century, when religion started to be examined scientifically instead of just theologically. Not that such scrutiny was readily applied to Christianity, but as the emerging science of religion scanned all the other religions explored around the world, the inclusion of Christianity in the analysis was unavoidable and at length unstoppable.

Max Müller, a 19th century pioneer of the scientific study of religion, was careful to point out that his findings related to "heathen" religions and gods, when presenting his idea that they were the results of a disease of language. Words depicting ordinary natural phenomena turned by time into mythology, in which "heathen gods are nothing but poetical names, which were gradually allowed to assume a divine personality never contemplated by their original inventors."[25]

Müller's reasoning is not far from that of Euhemerus, but Müller transforms it to encompass all of nature, not just enhanced descriptions of prominent people of the past. Some of his examples are obvious, such as the planets being turned into deities. That is the case in many more mythologies than those of Ancient Greece and Rome.

The English anthropologist Edward B. Tylor, who is regarded as a major pioneer in the fields of cultural as well as social anthropology, made a lasting impression on the research of mythology with his work Primitive Culture, published in 1871. Tylor's main theory, on which he based his analysis of mythology as well as other cultural manifestations of what he called primitive society, is that of animism, the belief that there is life in many or all objects and phenomena.

This aspect dominates his text. Of the book's 19 chapters, seven are devoted to the theme of animism already in their titles. Still, it appears frequently in the other chapters, too. Tylor regarded animism to be the cause of mythology as a whole:

First and foremost among the causes which transfigure into myth the facts of daily experience, is the belief in the animation of all nature, rising at its highest pitch to personification.[26]

Thus, the gods as well as the other active characters of myths were born out of animism. Tylor saw it as an application of analogy — what seems like something must in some way be that something. What we use as poetic metaphor and such, had quite another significance in the distant past: "Analogies which are but fancy to us were to men of past ages reality."[27]

He compared it to the experience of the child, unable to make distinctions between reality and the impressions of it. He quoted from Victor Hugo's Les Misérables about Cosette and her doll, "imagine that something is someone."[28] Tylor likened the intellect of the human species in its early stage to that of children and childlike ideas, "in our childhood we dwelt at the very gates of the realm of myth."[29]

To Tylor, this childhood is something that civilized man of the Western world has left behind, and he was far from alone at that time to think so. It can be debated. A more interesting line of thought is that of childhood per se, in all times and all cultures, and what makes children so delighted to let their minds wander into the realm of myths. They don't seem to do so out of fear or angst, but with joy.

Freud's explanation of the emergence and role of mythology lacks that ingredient of joy completely, although it is evident among adults as well. Mythology has always intrigued us and worship has more often than not been celebratory. This, too, puts Freud's theory into question.

Another pioneer of the scientific study of mythology was James G. Frazer, whose writing Freud refers to frequently in Totem and Taboo. Frazer's major contribution to the study of myth was his extensive work The Golden Bough from 1890, with much expanded editions following.

Frazer's basic theory was that primitive man long ago was trying magic, first and foremost in fertility cults, as a means to control aspects of life that were beyond hands-on control. This magic evolved into religion, which in turn much later evolved into science. So, he defined magic as a kind of pseudo-science. When it failed to provide sufficient results, people had to accept the power of fate, and magic was replaced by prayers and sacrifice.[30]

Yet, regarding the very origin of religious beliefs, Frazer later developed the firm conviction that it depended on the fear of the dead. He stated it very clearly in the preface to the abridged edition of The Golden Bough, published in 1922, "the fear of the human dead, which, on the whole, I believe to have been probably the most powerful force in the making of primitive religion."[31]

Later, he wrote a book on this subject, The Fear of the Dead in Primitive Religion, where he repeated his credo, "there can be little doubt that the fear of the dead has been a prime source of primitive religion."[32] This book was his last major work.

It should be noted that he was not talking about the fear of death, but living people's fear of those who had died. It would be so much easier to follow his chain of thought if he were to describe the significance of the fear of death — not the dead — in the cults, rituals, and mythologies of religions.

Frazer's theory about the fear of the dead would not have reached Freud when he wrote Totem and Taboo, but that about magic developing into religious worship most likely had. Frazer and other anthropologists writing about mythology were not exclusively examining the monotheisms. Therefore, they were able to see other patterns in the emergence of religions and their rites than Freud allowed in his perspective.

The major difference between those anthropologists and Freud is that where the former speculated about religion diversifying and developing through time, much like the evolution discovered by Charles Darwin, Freud presented religion as something once born, for one reason, and that was it. Of course, this is only possible to claim at all if just looking at the Abrahamic monotheisms, which do have one common source.

Something Worth Pondering?

Although Freud's theory about the origin of religion being one and the same for all religions is its major weakness, it remains a perspective worth investigating.Beliefs in supernatural powers, executed by more or less anthropomorphic beings whose existence elude scrutiny, are found all through known history and in any society. These traditions certainly differ so much that terms like religion and gods fail to describe them all adequately, but they do share some common denominators. Freud's examination was an effort to describe what they may have in common at their roots. He failed to prove that his explanation was the right one, but he pointed out the value of the search.

For example, human fear of the unknown is evident in every mythology I have come across. Death is not the least of those fears. Maybe a theory based on human anguish about death would further our understanding of how religions appeared. Death is something we know that none of us can escape, and yet we really know nothing about where that passage might or might not lead. All mythologies treat death extensively and no society in recorded history is completely free of rites related to its occurrence.

Christianity and Islam have soothing assurances about an afterlife — and, of course, nightmarish alternatives for the wicked. That can be found in polytheism as well. But contrary to the idea of blissful existence in the beyond, several of the ancient mythologies depict a most gruesome afterlife, which could in no way be comforting for the believer. Often the realm of the dead is a netherworld, from which there is no escape and in which there is no solace.

The Epic of Gilgamesh is the oldest substantial work of literature remaining. Its most ancient version is from the 18th century BC, but the text is probably a few hundred years older than that. Gilgamesh's companion Enkidu, who is ridden by fear of imminent death, visits the netherworld in a dream. It is not a pleasant sight.

He bound my arms like the wings of a bird,

to lead me captive to the house of darkness, seat of Irkalla:

to the house which none who enters ever leaves,

on the path that allows no journey back,

to the house whose residents are deprived of light,

where soil is their sustenance and clay their food,

where they are clad like birds in coats of feathers,

and see no light, but dwell in darkness.[33]

The Egyptian Book of the Dead is a collection of texts by priests over a long period, where the oldest parts are from the 3rd millennium BC. It is a manual of sorts for how to manage in the realm of the dead by methods mainly of magical spells and offerings. It is not an easy matter, and great perils are at stake. What is needed to navigate somewhat safely through that domain is hardly accessible to others than the most fortunate and wealthy — initially none other than the pharaoh.

Success in this complicated quest would lead to a formidable eternal life as someone akin to the gods. According to some texts, probably of later date, the final test is a weighing of the heart ritual, measuring sinfulness. But against this, too, there are magic spells guaranteeing a good outcome, whatever deeds one has committed in life.

Although there are terrible monsters to overcome along the way, as well as many precautions absolutely necessary in order to proceed, there is no explicit mention of the outcome for failure — except being killed by one of those monsters. What is implied is how crucial it is to avoid failure. Without the tools of the book, the afterlife has no hope. So, failure is out of the question, which is probably why it is not described in any detail. E. A. Wallis Budge, translator of the texts, writes:

Of the condition of those who failed to secure a life of beautitude with the gods in the Sekhet-Aaru of the Tuat, the pyramid texts say nothing, and it seems as if the doctrine of punishment of the wicked and of the judgment which took place after death is a development characteristic of a later period.[34]

Still, the mythology of the book serves as a setting in which safe travel to a splendid afterlife is possible. In this way, it brings hope of something good waiting on the other side of death. A belief of that kind must be comforting — at least to the pharaoh.

Some other mythologies are much more generous. There is the Norse belief in the afterlife Valhalla, where the Vikings can forever do battle each day and feast each night — as long as they have died in battle. That would be heaven to a Viking.

Every morning, when they have dressed themselves, they take their weapons and go out into the court and fight and slay each other. That is their play. Toward breakfast-time they ride home to Valhal and sit down to drink.[35]

Even Buddhism, with its principle of reincarnation, soothes the mind of man worrying about death. It explains what will happen, and even though the ultimate ideal is ceasing to exist, its believers will have the benefit of knowing what is ahead. They can also take comfort in being reborn before that ultimate step.

The Indian religions were not the only ones to contain the idea of reincarnation. Several of the Greek philosophers had a similar idea, calling it metempsychosis, starting with Pherecydes of Syros in the 6th century BC. Pythagoras, said to be his pupil, developed this idea more. Diogenes Laertius even has him inventing it:

He was the first, they say, to declare that the soul, bound now in this creature, now in that, thus goes on a round ordained of necessity.[36]

Pythagoras's own metempsychosis was a trick played on the gods to achieve a kind of immortality:

This is what Heraclides of Pontus tells us he used to say about himself: that he had once been Aethalides and was accounted to be Hermes' son, and Hermes told him he might choose any gift he liked except immortality; so he asked to retain through life and through death a memory of his experiences. Hence in life he could recall everything, and when he died he still kept the same memories.[37]

By this device Pythagoras protected what is the essence of immortality — the preservation of one's memories. There is no point to an afterlife that lacks recollection of previous experiences. Strictly speaking, without remembering the former life it is no afterlife at all — just another life.

Plato, too, expressed belief in metempsychosis. It is through his writing that the subject reached attention in the Western world. He regarded the soul as indestructible, wherefore it would wander on after the death of the body to occupy another body. Since souls are indestructible, there is also a fixed number of them:

But if it is so, you will observe that these souls must always be the same. For if none perishes they could not, I suppose, become fewer nor yet more numerous. For if any class of immortal things increased you are aware that its increase would come from the mortal and all things would end by becoming immortal.[38]

All those belief systems we call religions have in common that they do — one way or other — explain what happens when we die. Even if that is something far worse than what life offers, at least it is a kind of clarification. What can be more frightening than the complete unknown? This is what Shakespeare pointed out in the famous monologue in which Hamlet contemplates suicide:

Who would fardels bear,

to grunt and sweat under a weary life,

but that the dread of something after death,

the undiscover'd country from whose bourn

no traveller returns, puzzles the will,

and makes us rather bear those ills we have,

than fly to others that we know not of.[39]

And there is much more of the unknown explained by mythology. For example, myths tell how it all began and how it will end in the future, why seasons change, why day is followed by night, what wakes up the winds, what makes rain fall, and just about everything else incomprehensible to people of our distant past.

In particular, the unpredictable blows of fate were not only explained as the work of deities hidden from view, but there were methods of magic or worship by which to please those deities and gain a better fortune. Something could be done even about things that were totally incomprehensible.

In short, questions that arose in the wondering human mind could be answered by its own imagination.

There are, most definitely, common denominators to be found in the origins of the religions. But the patricide of Freud's theory is not one of them.

Notes

- Sigmund Freud, Totem and Taboo, transl. A. A. Brill, New York 1918, p. iii. ↑

- The English title, published in 1916, was Psychology of the Unconscious. ↑

- Sigmund Freud & Otto Rank: The Letters of Sigmund Freud and Otto Rank: Inside Psychoanalysis, edited by E. James Lieberman and Robert Kramer, Baltimore 2012, pp. 37f. ↑

- A. L. Kroeber, "Totem and Taboo: An Ethnologic Psychoanalysis," American Anthropologist vol. 22, 1920, p. 48. ↑

- Ibid., pp. 51-53. ↑

- Freud, Totem and Taboo, p. 165. ↑

- Ibid., p. 258. ↑

- John Long, Voyages and Travels of an Indian Interpreter and Trader, London 1791, p. 87. He spelled it totamism. ↑

- Andrew Lang, Myth, Ritual & Religion, volume I, London 1887, p. 59. Also in Freud, Totem and Taboo, p. 5 (footnote). ↑

- Freud, Totem and Taboo, pp. 5f. ↑

- Ibid., pp. 205f. ↑

- Charles Darwin, The Variation of Animals and Plant under Domestication, vol. 2, 2nd edition, London 1875, p. 103. The 1st edition was published in 1868. ↑

- Freud, Totem and Taboo, p. 234. ↑

- Quoted from James Jasper Atkinson, Primal Law, published in 1903 in a volume also containing Andrew Lang, Social Origins, which dealt with totemism, too. Andrew Lang & James Jasper Atkinson, Social Origins & Primal Law, London 1903, pp. 220f. ↑

- Freud, Totem and Taboo, p. 207. ↑

- Ibid., p. 235. ↑

- Ibid., p. 237. ↑

- Ibid., p. 239. ↑

- Ibid., p. 265. ↑

- Carl G. Jung, The Theory of Psychoanalysis, New York 1915, p. 69. The German original, Versuch einer Darstellung der psychoanalytischen, was published in 1913. ↑

- Sigmund Freud, Sexuality and the Psychology of Love, New York 1963, p. 141. ↑

- Ibid., pp. 197f. ↑

- 1 Corinthians 14:34-35, King James Bible. ↑

- Freeman, Kathleen, The Pre-Socratic Philosophers, Oxford 1946, p. 157. ↑

- Max Müller, Lectures on the Science of Language, London 1861, p. 11. ↑

- Edward B. Tylor, Primitive Culture: Researches into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Art, and Custom, vol. 1, London 1871, p. 258. ↑

- Ibid., p. 269. ↑

- "Se figurer que quelque chose est quelqu'un." Ibid., p. 258. ↑

- Ibid., p. 257. ↑

- James G. Frazer, The Golden Bough: A Study in Comparative Religion, vol. 1, London 1890, p. 31. ↑

- James G. Frazer, The Golden Bough: A study of magic and religion, abridged edition, New York 1922, p. vii. ↑

- James G. Frazer, The fear of the dead in primitive religion, London 1933, p. v. ↑

- The Epic of Gilgamesh, transl. Andrew George, London 1999, p. 61. ↑

- E. A. Wallis Budge, The Book of the Dead: The Papyrus of Ani, first edition 1895, New York 1967, p. cvi. ↑

- The Younger Edda, transl. Rasmus B. Anderson, Chicago 1880, p. 107. The Eddas are collections of Norse mythology and legends written down by Snorri Sturluson in the 13th century. ↑

- Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, vol. 2, transl. R. D. Hicks, London 1925, p. 333. ↑

- Ibid., p. 323. ↑

- Plato, Republic, transl. Paul Shorey, volume 2, book X:611, London 1942, p. 479. ↑

- William Shakespeare, "Hamlet, Prince of Denmark," act 3 scene 1, The Complete Works of William Shakespeare, London 1973, p. 862. ↑

Sigmund Freud on Myth and Religion

1: Introduction

2: Totem and Taboo

3: The Future of an Illusion

4: Civilization and Its Discontents

5: Moses and Monotheism

6: The Stubborn Mind

Freudians on Myth and Religion

Introduction

Sigmund Freud

Freudians

Karl Abraham

Otto Rank

Franz Riklin

Ernest Jones

Oskar Pfister

Theodor Reik

Géza Róheim

Helene Deutsch

Erich Fromm

Literature

This text is an excerpt from my book Psychoanalysis of Mythology: Freudian Theories on Myth and Religion Examined from 2022. The excerpt was published on this website in February, 2026.

MYTH

Introduction

Creation Myths: Emergence and Meanings

Psychoanalysis of Myth: Freud and Jung

Jungian Theories on Myth and Religion

Freudian Theories on Myth and Religion

Archetypes of Mythology - the book

Psychoanalysis of Mythology - the book

Ideas and Learning

Cosmos of the Ancients

Life Energy Encyclopedia

On my Creation Myths website:

Creation Myths Around the World

The Logics of Myth

Theories through History about Myth and Fable

Genesis 1: The First Creation of the Bible

Enuma Elish, Babylonian Creation

The Paradox of Creation: Rig Veda 10:129

Xingu Creation

Archetypes in Myth

About Cookies

My Other Websites

CREATION MYTHS

Myths in general and myths of creation in particular.

TAOISM

The wisdom of Taoism and the Tao Te Ching, its ancient source.

LIFE ENERGY

An encyclopedia of life energy concepts around the world.

QI ENERGY EXERCISES

Qi (also spelled chi or ki) explained, with exercises to increase it.

I CHING

The ancient Chinese system of divination and free online reading.

TAROT

Tarot card meanings in divination and a free online spread.

ASTROLOGY

The complete horoscope chart and how to read it.

MY AMAZON PAGE

MY YOUTUBE AIKIDO

MY YOUTUBE ART

MY FACEBOOK

MY INSTAGRAM

STENUDD PÅ SVENSKA

Stefan Stenudd

About me

I'm a Swedish author of fiction and non-fiction books in both English and Swedish. I'm also an artist, a historian of ideas, and a 7 dan Aikikai Shihan aikido instructor. Click the header to read my full bio.

Archetypes of Mythology

Archetypes of Mythology Psychoanalysis of Mythology

Psychoanalysis of Mythology