Sigmund Freud:

|

by Stefan Stenudd |

Also, he based his understanding of religion solely on the Judeo-Christian monotheism with a fatherly almighty at the top, although he was far from ignorant of so many other religions to which his assumptions just were not applicable. Furthermore, his perspective on religion and its causes was exclusively male, where women were just bystanders with no active part in it.

He had made up his mind about the matter already when writing Totem and Taboo in 1913, being in his fifties, and stuck with it until the end of his life in 1939. During that time, he presented no new evidence, nor did he succeed in convincing any experts in the field of religion — just his own disciples, and not even all of them. Nothing could change his mind or even make him nuance his claims. For a propagator of science and its vast importance to society, that is absurdly stubborn.

If he had psychoanalyzed himself, he must have concluded that he had serious father issues, causing his firm opinion. Well, according to biographers and some passages in his texts, he did to some extent study himself like he would a patient. Still, it led to nothing but his strengthened belief in his own explanations. His thoughts were clouded by his commitment to what he regarded as his unique discoveries, which he was certain to be worthy of praise. Presumably his judgment was also influenced by a complicated relation to his father, but that is outside the scope of this book.

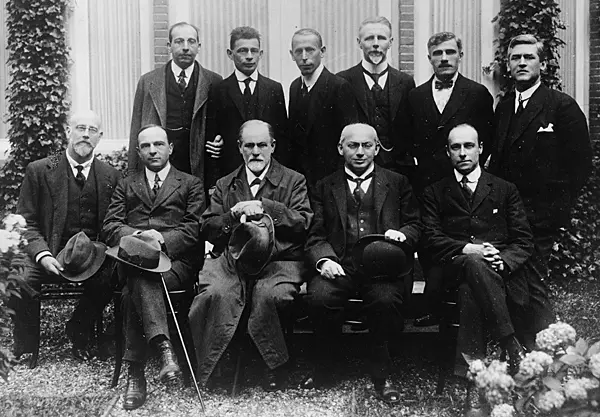

The 6th international Congress of psychoanalysis in The Hague 1920. Left to right, seated: Jan Van Emden, Ernest Jones, Sigmund Freud, Sandor Ferenczi, John Carl Flügel. Standing: Hanns Sachs, Otto Rank, Karl Abraham, Oscar Rie, Adolph Stern, Johan van Ophujisen.

His stubbornness seems to have been contagious. As will be seen in the following pages, most of his students were just as stubborn, sticking to their master's paradigm without no more evidence than he had. Although himself an atheist, Freud's teaching was to him and to his students akin to theology. Not to be questioned. Those who did, like most notably Carl G. Jung, were regarded as pariah.

That is strange behavior from people who regarded themselves as experts on the human psyche.

The Secret Committee

A flagrant example of Freudian efforts to silence critique and discard opposition within the movement was the so-called Secret Committee, the inner circle of Freud's most loyal followers.What led up to it was that two prominent students of Freud, Alfred Adler and Carl G. Jung, started to deviate from his teaching. This is how he describes it in his autobiography:

In Europe during the years 1911-13 two secessionist movements from psycho-analysis took place, led by men who had previously played a considerable part in the young science, Alfred Adler and C. G. Jung. Both movements seemed most threatening and quickly obtained a large following.[1]

He goes on to explain that they wanted to "escape" recognizing the importance of infant sexuality and the Oedipus complex, Jung by attempting the interpretation of "an abstract, impersonal and non-historical character" and Adler by tracing "the formation both of character and of the neuroses solely to men's desire for power and to their need to compensate for their constitutional inferiority."

Freud reacted strongly to their deviations, having none of it. When they went their own way, they were excluded from his movement, regarded as outcasts. His own version of what passed, though, was deceptively idyllic:

The criticism with which the two heretics were met was a mild one; I only insisted that both Adler and Jung should cease to describe their theories as 'psycho-analysis'.[2]

But calling them heretics, as if Freud's teaching was of divine origin, is presumptuous, to say the least. And by refusing to allow their theories in the science he was so proud of having introduced, he revealed that he regarded it as solely his possession.

But that is not how science works. Freud's intolerance was utterly unscientific.

He admits to having been accused of intolerance, but defends himself by mentioning several psychoanalysts who stayed loyal to him and his ideas. To him, this is proof that he could not be intolerant:

I can say in my defence that an intolerant man, dominated by an arrogant belief in his own infallibility, would never have been able to maintain his hold upon so large a number of intelligent people.[3]

That can certainly be discussed. Whatever intelligence is, it is not always accompanied by wisdom, or for that matter by integrity. That was soon to be shown.

In 1912, when both Adler and Jung had deviated from the doctrine, Ernest Jones suggested in a letter to Freud what was to be the Secret Committee. Freud responded enthusiastically to the idea:

What took hold of my imagination immediately is your idea of a secret council composed of the best and most trustworthy among our men to take care of the further development of and defend the cause against personalities and accidents when I am no more.[4]

Although Freud was only in his fifties at the time, he was so preoccupied by his legacy that he repeated a few lines down in the same letter: "I daresay it would make living and dying easier for me if I knew of such an association existing to watch over my creation."

The whole thing had a scent of boyish adventure to it, which Freud was aware of from the start:

I know there is a boyish, perhaps romantic element too in this conception but perhaps it could be adapted to meet the necessities of reality.

That did not stop him from adding romantic elements to it. When the Secret Committee was formed, initially consisting of Ernest Jones, Sándor Ferenczi, Hanns Sachs, Karl Abraham, and Otto Rank, he gave each of them a golden ring with a select motif from Roman mythology. They met in Vienna in May 2013, committing to the secret task of protecting Freud's dogma. He told Ferenczi that he was very happy with his "adopted children."[5]

Alfred Adler's departure from the Freudian doctrine was frustrating to his colleagues as well as to Freud, but it was definitely Carl G. Jung's break that shook them the most — Freud in particular. He had regarded Jung as his successor, a crown prince of sorts, and felt evident affection for him.

It was mutual until it went sour, followed by the kind of bitterness and disappointment similar to the end of a love story. Their correspondence indicates that the break had much more to do with their personal relation than with scientific disagreements, though both avoided that angle of the issue in their public writing. The crescendo of their quarrel came with Jung's letter to Freud in December 1912, where he wrote:

If ever you should rid yourself entirely of your complexes and stop playing the father to your sons and instead of aiming continually at their weak spots took a good look at your own for a change, then I will mend my ways and at one stroke uproot the vice of being in two minds about you.[6]

These insults thinly disguised as a peace offering, whether accurate or not about Freud's behavior, soon led to their definite separation. Still, neither of them would scorn the other publicly. Jung continued for some time to express praise for Freud in his writing, and the latter stayed silent but asked Sándor Ferenczi to write a critique of Jung's work. Freud did not do so until Jung had formally broken all his ties with the psychoanalytic movement, in 1914.

That year, Freud wrote two texts criticizing the psychological theories of both Adler and Jung: On Narcissism and The History of the Psychoanalytic Movement, initially published in German. He was not kind to his former crown prince. In the latter text, after mentioning that he had seen Jung as his successor, his words get harsher. He claims that he had made Jung give up "certain race prejudices which he had so far permitted himself to indulge."[7] That is a grave accusation, and rather uncalled for if he had made Jung change his mind. Why, then, bring it up? He continues:

I had no notion then that in spite of the advantages enumerated, this was a very unfortunate choice; that it concerned a person who, incapable of tolerating the authority of another, was still less fitted to be himself an authority, one whose energy was devoted to the unscrupulous pursuit of his own interests.

Considering Freud's own behavior, the same could be said about him. Later in the text, he objects to Jung's continued use of the term psychoanalysis although he has deviated from Freud's theories:

I am naturally entirely willing to admit that any one has the right to think and to write what he wishes, but he has not the right to make it out to be something different from what it really is.[8]

But no person can own a science, nor dictate how it may progress. Freud regarded psychoanalysis as his property, which should never deviate from the paradigms he had set. Then it is no longer science, but dogma. The members of the Secret Committee as well as many other psychoanalysts were strangely blind to the absurdity of Freud's claim.

Nevertheless, Jung soon shifted to the expression analytical psychology for his approach to the science and its methods.

In 1919, on Freud's suggestion, Max Eitingon was added to the Secret Committee, which continued its covert work into the late 1920's, but not without some turmoil. In 1927, when Karl Abraham had died and Otto Rank had left, continued disagreements within it led to its dissolution.

The Secret Committee with Sigmund Freud in 1922. Sigmund Freud, Sándor Ferenczi, and Hanns Sachs. Standing: Otto Rank, Karl Abraham, Max Eitingon, Ernest Jones.

The same year, though, it was reconstituted and given an official status as a governing body of the International Association of Psychoanalysis, no longer secret. It consisted of Freud's daughter Anna Freud, who had previously replaced Otto Rank, Eitingon, Ferenczi, Jones, and Johann van Ophuijsen. The only remaining members from 1912 were Ferenczi and Jones.[9] In the early 1930's, Ferenczi got increasingly alienated, but he died in 1933 without having formally resigned. Then, out of the original committee, only Ernest Jones — the one who had come up with the idea of it — remained.

It is a strange story. The correspondence between Freud and the members of the committee is full of intrigue, insinuations, gossip, and slander. Frankly, it is a soap opera, way below what would be expected from men of science — but certainly not unique in such communities, though rarely as flagrant as here.

The members of the committee were just as anxious to please their master as he was craving their praise. The varying rivalry and hostility between them all, Freud included, dimmed their reason even on psychological matters. They lapsed into using their psychology as a weapon to harm each other.

In her book about the Secret Committee, Phyllis Grosskurth concludes:

The epic story of the Committee evokes Aristotelian pity and terror but, alas, the spectacle does not provide us with any healing catharsis. We are witnessing not actors on a stage but real people wreaking havoc on each other.[10]

It is no exaggeration to say that this behavior was the norm among these people, who were at the top of the psychoanalytical movement. That means it must have been approved and even encouraged by its authoritarian leader, Sigmund Freud. Those who were loyal to him conformed to it, as long as their loyalty remained. If he had opposed to it, so would they. He did not.

It may have been less blameworthy for scientists in other fields than his, who could excuse themselves for not having the knowledge to predict the effect. But as a psychologist, Freud could hardly claim to be unaware of the consequences of this mentality within his movement. There were more than enough warning signals of utter discomfort within his Secret Committee, not to mention those who were the targets of their scheming.

Freud's effort was to keep his science pure, by which he meant strictly committed to his ideas, but what it led to was making the whole thing stained — the movement as well as its scientific claims.

Notes

- Sigmund Freud, An Autobiographical Study, transl. James Strachey, London 1935 (originally published in 1925), p. 96. ↑

- Ibid., p. 97. ↑

- Ibid., p. 98. ↑

- Phyllis Grosskurth, The Secret Ring: Freud's Inner Circle and the Politics of Psychoanalysis, Reading 1991, p. 47. ↑

- Ibid., p. 52. ↑

- Ibid., p. 50. ↑

- Sigmund Freud, The History of the Psychoanalytic Movement, transl. A. A. Brill, New York 1917 (originally published in German 1914), p. 35. ↑

- Ibid., p. 52. ↑

- Grosskurth 1991, p. 192. ↑

- Ibid., p. 220. ↑

Sigmund Freud on Myth and Religion

1: Introduction

2: Totem and Taboo

3: The Future of an Illusion

4: Civilization and Its Discontents

5: Moses and Monotheism

6: The Stubborn Mind

Freudians on Myth and Religion

Introduction

Sigmund Freud

Freudians

Karl Abraham

Otto Rank

Franz Riklin

Ernest Jones

Oskar Pfister

Theodor Reik

Géza Róheim

Helene Deutsch

Erich Fromm

Literature

This text is an excerpt from my book Psychoanalysis of Mythology: Freudian Theories on Myth and Religion Examined from 2022. The excerpt was published on this website in February, 2026.

MYTH

Introduction

Creation Myths: Emergence and Meanings

Psychoanalysis of Myth: Freud and Jung

Jungian Theories on Myth and Religion

Freudian Theories on Myth and Religion

Archetypes of Mythology - the book

Psychoanalysis of Mythology - the book

Ideas and Learning

Cosmos of the Ancients

Life Energy Encyclopedia

On my Creation Myths website:

Creation Myths Around the World

The Logics of Myth

Theories through History about Myth and Fable

Genesis 1: The First Creation of the Bible

Enuma Elish, Babylonian Creation

The Paradox of Creation: Rig Veda 10:129

Xingu Creation

Archetypes in Myth

About Cookies

My Other Websites

CREATION MYTHS

Myths in general and myths of creation in particular.

TAOISM

The wisdom of Taoism and the Tao Te Ching, its ancient source.

LIFE ENERGY

An encyclopedia of life energy concepts around the world.

QI ENERGY EXERCISES

Qi (also spelled chi or ki) explained, with exercises to increase it.

I CHING

The ancient Chinese system of divination and free online reading.

TAROT

Tarot card meanings in divination and a free online spread.

ASTROLOGY

The complete horoscope chart and how to read it.

MY AMAZON PAGE

MY YOUTUBE AIKIDO

MY YOUTUBE ART

MY FACEBOOK

MY INSTAGRAM

STENUDD PĹ SVENSKA

Stefan Stenudd

About me

I'm a Swedish author of fiction and non-fiction books in both English and Swedish. I'm also an artist, a historian of ideas, and a 7 dan Aikikai Shihan aikido instructor. Click the header to read my full bio.

Archetypes of Mythology

Archetypes of Mythology Psychoanalysis of Mythology

Psychoanalysis of Mythology