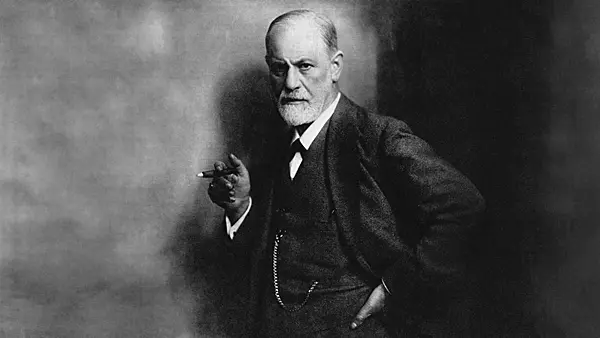

Sigmund Freud: Civilization and Its Discontents

Chapter 4 on his theories about mythology and religion examined by Stefan Stenudd

The Oceanic FeelingHe begins by confessing that there is one aspect of religion, which he neglected in the previous book. It is the overwhelming feeling it can bring to its believers, "a sensation of 'eternity', a feeling as of something limitless, unbounded, something 'oceanic'."[1]The observation is not his own, but was reported in a letter to him from an "exceptional" man, whom he does not name.[2] It was the French author Romain Rolland, with whom he corresponded for many years, in a letter dated December 5, 1927. Rolland spoke from personal experience, whereas Freud confesses that he cannot find that feeling in himself, which does not stop him from defining it:

That spectacular sensation is not exclusively religious, although it is understood as such when experienced in such a setting. Considering the characteristics of Freud's psychology, one would think he should compare it to the orgasm. But the closest he comes to that is seeing similarities to being in love.[4] Instead, using his definition above, he connects that oceanic feeling to a mind unable to separate the inner world from the outer one. It's all one. That is the mind of an infant:

Civilization or CultureBut Freud's book is not aimed at investigating the cause and effect of religion. His scope is wider. As the title implies, it is about man's ambiguous relation to society as a whole. It protects the individual from potential malice of others — Freud compares it to the child's need of a good father[7] — but that also means the individual's own urges and impulses are restrained. That is what causes the discontent.Freud's theories make frequent use of what he regarded as conflicting opposites, such as men's needs versus those of women, sons competing with their fathers, and personal impulses subdued by social norms. His focus here is the conflict between human nature and social order. The animalistic urges in men must be held at bay for civilization to appear and advance. Religion is one of the tools by which this is accomplished. In other words, the conflict he explores is that between nature and civilization. But that polarity is somewhat flawed. The term civilization suggests an advanced society, where the population is civilized, traditionally also connected to the city and its particular demands on its citizens. These words are all etymologically connected, implying the difference between urban and rural. The antonym to civilization would be something like barbarism or savagery, which is how Freud and many others at his time regarded people of the prehistoric past as well as indigenous tribes in the present. Another often used word was primitive. His comparison of the child's mentality vis-a-vis that of the adult points to the same idea of a development over time, which was seen as having been halted in the case of indigenous people. It is the difference between the primitive and the advanced, which was believed to be an accurate division of societies. They were societies, all of them, but some were developed and others remained in sort of an infantile state. The latter are still often categorized as underdeveloped, as if the only development a society can have is towards modern industrialism. That is definitely how Freud saw it, but his book is not comparing different societies. The opposite it describes is that between the individual and the collective, in particular the natural urges of the former versus the cultural condition of the latter. The conflict is between instinctual and regulated behavior. It is analogous to the expression made famous in the comic Calvin and Hobbes by Bill Watterson: "You can take the tiger out of the jungle, but you can't take the jungle out of the tiger." A wild tiger can be captured, but not tamed. So, the fundamental opposition Freud discusses in his book is the one between human nature and human culture. The German word he uses already in the title is Kultur, culture, which is possible to interpret as civilization. But for that there is the German word Zivilisation, which he did not use even once in his book. The word Kultur, on the other hand, is used over 60 times.[8] He presents the same definition of the concept as he used in The Future of an Illusion:

Words have lives of their own, making fixed and exclusive definitions of them precarious. One difference between the concepts of civilization and culture, though vague, is that the former is about structure and the latter about content. Where civilization points to how a society is organized, culture is about how we act in it, what we do with it. Another interesting difference, relevant in the context of Freud's book, is that not all societies can be described as civilizations, but they are all cultures. Freud's theory does not only concern the societies that have developed into what are called civilizations, but any human society demanding its individuals to adapt to it — and that is every society, whether ancient or contemporary, big or small, rural or urban. So, the English title of the book is slightly misleading. Still, Freud seems to have approved the use of civilization instead of culture. In a letter to the translator Joan Riviere, he pondered other words in the title, suggesting it to be Man's Discomfort in Civilization. She was the one coming up with the wording that was adopted.[10] There are additional complications with the title. It implies that some citizens are discontent, and accordingly others are not, as if immune. But in Freud's view on the human nature, it would be close to impossible for some to be completely content with the restrictions society puts on its members. There may be varied degrees of discontent, but it touches all. That is also what the German title, Das Unbehagen in der Kultur, implies — the discomfort, as Freud would have it in English, is universal.

The Pleasure of ConformingCertainly, society's demands on people are straining. That goes for any society at any time, as well as every member of it. The world literature is full of examples, from the epic of Gilgamesh and on. Anthropological studies have shown the same in any culture examined. No mystery there.As for the causes to this conflict, though, answers are uncertain, to say the least. Sigmund Freud's contribution has not reached an end to the quest. The most intriguing question is why humans would at all form societies that discomfort them. Freud claims that it is to protect them from their own malice. They gang together so that they can overpower any one person among them who is a threat:

Freud's analysis of this dilemma has one major flaw. It is based on the assumption that human urges are personal. They are not. There is no urge greater than that of being included and accepted among fellow humans. We may be beasts, but we are social beasts. That is at the core of our nature. So, the joy of inclusion vastly overtrumps the inconveniences of conforming. Actually, to any social beast, conforming is a pleasure, not an annoyance. This basic animalistic tendency predates every religion and elaborate social structure. The extreme introverted perspective of psychoanalysis is probably what made Freud underestimate the social character of individual aspirations. We fulfill ourselves by the approval of others. It is so essential to our lives that we are even prepared to give up life itself for it. Discussing the Jesus quote about loving one's neighbors as oneself, Freud states that "nothing is so completely at variance with original human nature as this."[13] He could not be more wrong. Compassion is embedded in human nature. We feel the pains and pleasures of others as if they were our own. Freud's book claims that the discontent lies in the self-restraint of conforming to society, but that is joyous. The real discontent lies in not being able to conform completely. Individual satisfaction is bitterly unsatisfactory if perceived to be contrary to social demands and expectations. That is when the sense of guilt sets in — not when following the social norms, but when deviating from them. That is where the theory of the Oedipus complex collapses. Sons joining to revolt against a father who is the oppressor of a whole tribe are not tormented by their action, but they would be if their fear hindered them from putting an end to that single man's dominance. It is deeply rooted in the human nature that the interest of the collective surpasses that of any individual. When this is not upheld is when guilt sets in. So, in Freud's Oedipus scenario, the sons would really have been utterly frustrated until they finally acted, and then at peace. They freed the tribe of a tyrant. Consequently, such a patricide could never have been the origin of religion.

Notes

Sigmund Freud on Myth and Religion

Freudians on Myth and Religion

This text is an excerpt from my book Psychoanalysis of Mythology: Freudian Theories on Myth and Religion Examined from 2022. The excerpt was published on this website in February, 2026.

MYTH

IntroductionCreation Myths: Emergence and MeaningsPsychoanalysis of Myth: Freud and JungJungian Theories on Myth and ReligionFreudian Theories on Myth and ReligionArchetypes of Mythology - the bookPsychoanalysis of Mythology - the bookIdeas and LearningCosmos of the AncientsLife Energy EncyclopediaOn my Creation Myths website:

Creation Myths Around the WorldThe Logics of MythTheories through History about Myth and FableGenesis 1: The First Creation of the BibleEnuma Elish, Babylonian CreationThe Paradox of Creation: Rig Veda 10:129Xingu CreationArchetypes in MythAbout CookiesMy Other WebsitesCREATION MYTHSMyths in general and myths of creation in particular.

TAOISMThe wisdom of Taoism and the Tao Te Ching, its ancient source.

LIFE ENERGYAn encyclopedia of life energy concepts around the world.

QI ENERGY EXERCISESQi (also spelled chi or ki) explained, with exercises to increase it.

I CHINGThe ancient Chinese system of divination and free online reading.

TAROTTarot card meanings in divination and a free online spread.

ASTROLOGYThe complete horoscope chart and how to read it.

MY AMAZON PAGE

MY YOUTUBE AIKIDO

MY YOUTUBE ART

MY FACEBOOK

MY INSTAGRAM

STENUDD PÅ SVENSKA

|

Archetypes of Mythology

Archetypes of Mythology Psychoanalysis of Mythology

Psychoanalysis of Mythology