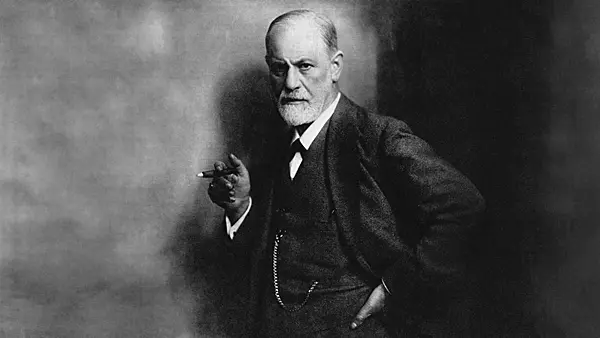

Sigmund Freud:

|

by Stefan Stenudd |

If anything, he proclaims it with even less reservation, stating that his conviction "has only become stronger since." He continues:

From then on I have never doubted that religious phenomena are to be understood only on the model of the neurotic symptoms of the individual, which are so familiar to us, as a return of long forgotten important happenings in the primaeval history of the human family, that they owe their obsessive character to that very origin and therefore derive their effect on mankind from the historical truth they contain.[1]

At least, he points out already with the title of his book that his speculations mainly concern monotheism. Still, as in the quote above, he keeps on claiming that his findings apply to all religion, and not just Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

The Story of the Patricide

Freud gives a narrated form of the primeval event of the father murder, more explicit and detailed than in Totem and Taboo. He begins with the following reservation, which had only been vaguely implied in the previous book:

The story is told in a very condensed way, as if what in reality took centuries to achieve, and during that long time was repeated innumerably, had only happened once.[2]

Certainly, it has the flavor and characteristics of a story — or a myth. Because of its fluent form, its added details compared to the version in Totem and Taboo, and its striking similarity to many myths, I repeat it below in its entirety,[3] inserting a few comments in between:

The strong male was the master and father of the whole horde: unlimited in his power, which he used brutally. All females were his property, the wives and daughters in his own horde as well as perhaps also those robbed from other hordes. The fate of the sons was a hard one; if they excited the father's jealousy they were killed or castrated or driven out.

Castration was not specified as a threat to the sons in Totem and Taboo, but in Moses and Monotheism it is mentioned also in relation to individual neurotic behavior, where Freud sees the fear of castration as a significant component. He continues his narrative:

They were forced to live in small communities and to provide themselves with wives by robbing them from others.

The robbing of wives was not mentioned in Totem and Taboo. Instead, it was implied that the outcast sons turned to homosexual relations among themselves and that this formed bonds between them, forging them together so that they found the courage to revolt against the father.

Moses and Monotheism gives no clue as to why this important ingredient in the bonding of the sons — also effective in the society they form after their revolt — is now abandoned from his speculations.

Then one or the other son might succeed in attaining a situation similar to that of the father in the original horde. One favoured position came about in a natural way: it was that of the youngest son who, protected by his mother's love, could profit by his father's advancing years and replace him after his death.

There is no mention of this fortunate opportunity of the youngest son in Totem and Taboo.

An echo of the expulsion of the eldest son, as well as of the favoured position of the youngest, seems to linger in many myths and fairy tales.

In this book Freud refers rather frequently to myths, also using examples from the Bible, whereas in Totem and Taboo he referred almost exclusively to ritual and anthropological observations.

He finishes his account of the primeval patricide, with the added event of the father being devoured:

The next decisive step towards changing this first kind of "social" organization lies in the following suggestion. The brothers who had been driven out and lived together in a community clubbed together, overcame the father and according to the custom of those times all partook of his body.

Freud also expands a little on the concept of a mother goddess and a hint of a matriarchy, partly related to the affection of the sons for their mother: "A good part of the power which had become vacant through the father's death passed to the women; the time of the matriarchate followed."[4] This matriarchy, he explains, was short-lived. A patriarchy returned, though not as potent as the original one.[5]

Collective Neurosis

In Moses and Monotheism, Freud expands and clarifies his theory somewhat. He specifies the stages gone through by mankind as a whole, comparing them to the individual neurotic stages of "early trauma — defense — latency — outbreak of the neurosis — partial return of the repressed material."[6]The analogy makes additional sense, since he claims that "the genesis of the neurosis always goes back to very early impressions in childhood."[7] Also mankind's patricide supposedly took place at an early stage, a childhood in the development of the human species. He describes the process:

That is to say, mankind as a whole also passed through conflicts of a sexual-aggressive nature, which left permanent traces but which were for the most part warded off and forgotten; later, after a long period of latency, they came to life again and created phenomena similar in structure and tendency to neurotic symptoms.[8]

The latency mentioned, existing both in the individual and the collective, is a sort of mental period of incubation, in which the traumatic event is forgotten to the conscious mind. But it remains unconsciously and gains strength, so that when it erupts, it is much more potent than it was at the time of the traumatic event:

It is specially worthy of note that every memory returning from the forgotten past does so with great force, produces an incomparably strong influence on the mass of mankind and puts forward an irresistible claim to be believed, against which all logical objections remain powerless very much like the credo quia absurdum.[9]

He compares this phenomenon to the delusion in a psychotic person, having a long-forgotten core of truth that upon reemerging becomes both distorted and compulsive.[10]

Latency of Memories

As a consequence of this latency, Freud needs to explain how something forgotten can remain through generations, to emerge in people as a very vivid and powerful memory of sorts.In Totem and Taboo, he supposed no forgetting of the patricide. On the other hand, he did not specify that the memory was kept through the generations. What was implied was an established totemism, containing the trauma of the patricide. This totemism continued to be obeyed, long after the actual event had been forgotten.

In Moses and Monotheism, he introduces latency, the suppressed memory able to reemerge, and therefore he needs to explain this process. Doing so, he comes strikingly close to Carl G. Jung's theories of the collective unconscious and the archetypes.

Freud states very clearly that people did forget, "in the course of thousands of centuries," about the initial patricide. So, how could that forgotten memory return? He uses the analogy with the individual, whose traumatic memory is repressed, buried deep in the unconscious, but has not disappeared. It can reemerge. When doing so, it has the same great force suggested about mankind as a whole. Both the individual and the collective have this ability:

I hold that the concordance between the individual and the mass is in this point almost complete. The masses, too, retain an impression of the past in unconscious memory traces.[11]

Such repressed memories may emerge in certain circumstances. With collective memories, this is most likely to happen when recent events are similar to those repressed.[12]

Archaic Heritage

Freud goes on to speculate that the individual does not only have personal memories stored in the unconscious, but also "what he brought with him at birth, fragments of phylogenetic origin, an archaic heritage."[13]He gives no explanation to how such a memory can be kept and transported through the generations, but finds support for it in observations of patients. When they react to early traumata, when an Oedipus or castration complex is examined, other than purely personal experiences seem to emerge. These make more sense if regarded as somehow inherited from earlier generations. Freud believes that they are part of what he calls the archaic heritage.

He also uses the argument of "the universality of speech symbolism,"[14] the ability to have one object symbolically substituted by another, which is particularly strong in children. This symbolism is also at work in dreams. Freud regards it as an ability inherited from the time when speech was developing. He is rather vague here, giving no examples of what kinds of objects and symbols he refers to.

He admits that the science of biology allows no acquired abilities to be transmitted to descendants, but boldly states: "I cannot picture biological development proceeding without taking this factor into account."[15]

Here he makes a comparison to animals, which he regards as fundamentally not very different from human beings in this respect. The archaic heritage of the "human animal" may differ in extent and character, but "corresponds to the instincts of animals." What makes a memory enter the archaic heritage is if it is important enough or repeated enough times, or both. Regarding the primeval patricide, he is quite certain:

Men have always known in this particular way that once upon a time they had a primaeval father and killed him.[16]

These theories have a striking resemblance to Jung's ideas of the collective unconscious and the archetypes. They even use similar arguments. Still, Freud makes no mention of Jung in the book, and no comparison with his models.

They were, of course, distanced since decades, and not on speaking terms — but Freud was aware of Jung's theories, which were well developed and widely known in the time of Moses and Monotheism. Freud must have recognized and pondered the similarities, but decided not to do so in writing.

Moses

Freud gives two examples from biblical events, on which to apply his theory — those of Moses and Jesus.About Moses, Freud claims that he was not Jewish but an Egyptian, befriending a Jewish tribe. Moses brought this tribe out of Egypt and converted it to his monotheistic religion, which was Pharaoh Ikhnaton's worship of the single sun god Aton.[17] It was introduced as the state religion of Egypt by the pharaoh in the 14th century BC. Soon after his demise, Egypt returned to its previous polytheism.

The reason for a monotheistic god at all appearing in an otherwise abundantly polytheistic culture, Freud finds in the imperialistic success of Egypt, immediately preceding the cult of Aton: "God was the reflection of a Pharaoh autocratically governing a great world empire."[18] Then Freud imagines a fate of Moses, similar to that of the primeval tyrant father:

The Jews, who even according to the Bible were stubborn and unruly towards their law-giver and leader, rebelled at last, killed him and threw off the imposed Aton religion as the Egyptians had done before them.[19]

Freud readily admits to have picked up the idea of Moses being killed by the Jewish tribe from a 1922 text by the German theologian and biblical archaeologist Ernst Sellin.[20] Both Sellin's theory and Freud's interpretation of it have been questioned by scholars.

Later on, in Freud's account of events, this Jewish tribe met and joined with another. As part of the compromise between the tribes, they adapted the worship of a volcano-god Jahve, influenced by the Arabian Midianites.[21]

In an effort to release themselves of the guilt for having killed Moses, the tribe insists on proclaiming him the father of this new monotheistic religion. In that way, they almost accomplish the father worship, which is the basis of Freud's theory on the origin of religion. By time, Jahve transforms to be more and more like the Egyptian god Aton.[22]

Jesus

Freud moves on to compare the story of Moses to that of Jesus, who was also sacrificed — but willingly. According to Freud, this was a symbolic amends for a primeval patricide:

A Son of God, innocent himself, had sacrificed himself — and had thereby taken over the guilt of the world.[23]

Jesus was proclaimed the son of god, i.e., the symbolic foremost son of the murdered father, the leader of the rebellion. He shouldered the responsibility for the father's death and suffered the equivalent punishment for it. Thus, the other sons, the rest of mankind, could in their minds feel forgiven by the father.

This is a process reminding of the Greek concept of catharsis, a cleansing that brings relief. Though Freud does not mention catharsis in the book, he was not unaware of its relevance to therapy. Its psychological application was introduced by Freud's mentor Josef Breuer in the 1880's, who called it the cathartic method. It was discussed by both in a book from 1895.[24]

To Freud, this sacrifice is unavoidable, because "a growing feeling of guiltiness had seized the Jewish people — and perhaps the whole civilization of that time — as a precursor of the return of the repressed material."[25]

To Freud, the primeval patricide is the true original sin. And to no surprise he sees the Holy Communion as an example of the totem feast, where the totem animal was ritually consumed.

Freud finds a significant difference in the fates of Moses and Jesus — the former being a father figure, the latter that of a son. Therefore, he sees the Mosaic religion as essentially focused on the father, whereas Christianity is focused on the son:

The old God, the Father, took second place; Christ, the Son, stood in His stead, just as in those dark times every son had longed to do.[26]

Judeo-Christian Relevance

No doubt, Christianity has several elements leading to somewhat similar impressions as those suggested by Freud. There is a sacrificed prophet teacher who repeatedly refers to an omnipotent father figure, a ritual meal of the martyr's flesh and blood, et cetera. There is also the desperate cry on the cross:"My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?"[27]

That would seem like a vindictive father. Jesus is quoting from Psalms 22 of the Old Testament, which describes a person in utter misery, despised and mocked by his fellow men, crying for God's aid but not getting it. He promises to praise God wide and loud if he gets saved. Psalms 22 doesn't reveal who asks the question or how that works out, but the desperate call for help and promise to repay it is nothing unfamiliar.

The killing and dividing of a primeval being is a common motif among creation myths. Oddly, it is not used as an example by Freud, although he must have come across such examples in his studies of mythology through Frazer and others. On the other hand, it is also easy to find mythologies with little or no trace of such a beginning.

Freud's theory seems more plausible in the sphere of Judeo-Christian religion, where a sole high god with male traits is worshipped. In religions swarming with gods of both genders, the conclusion makes far less sense.

Freud's religion is a male one, which he readily admits already in Totem and Taboo: "In this evolution I am at a loss to indicate the place of the great maternal deities who perhaps everywhere preceded the paternal deities."[28] He suggests that maternal goddesses dominated prior to the patricide, but were substituted with a high father god as a result of it. That in turn led to society as a whole evolving into patriarchy. The fatherless state after the patricide was replaced by a new patriarch.

That would risk the whole thing happening all over. But Freud sees a difference in the new patriarchy:

Now there were patriarchs again but the social achievements of the brother clan had not been given up and the actual difference between the new family patriarchs and the unrestricted primal father was great enough to insure the continuation of the religious need, the preservation of the unsatisfied longing for the father.[29]

Again, this chain of events is likelier, to say the least, in a society with a monotheistic religion, like the Judeo-Christian sphere. In Moses and Monotheism, he slightly altered his views on a mother goddess and a matriarchy, as mentioned above.

Guilt, too, is much more present in Judeo-Christian religion than in many others. This part of Freud's theory is even weaker than that about an actual battle between father and sons.

The concept of guilt felt and punished for generations is expressed repeatedly in the Bible. But in a time preceding the Bible, as well as in cultures free of its influence, we have little to confirm such persistence and dominance of that emotion. Instead, history tells us that people did not have that much trouble ridding themselves of any guilt, even when performing worse acts than killing a tyrant father.

Certainly, there are emotions that torment all members of our species, and rule over many of our actions. But Freud fails to prove that guilt is one of them, outside of his own cultural frame of reference.

No Cure for Oedipus

In spite of its flaws, Freud's bold thesis gives food for thought. Certainly, sexuality, death, and the complications of blood relations appear as themes in countless myths — as they do just about constantly in our minds.Several species, including mankind, are subject to lots of struggles in the process of reproduction. Males compete over the females, often violently. A strong male might not be satisfied by a first choice only, but would strive to exclude the other males completely from approaching the females. If any species were to find the solution of suppressed males joining and thereby overpowering the leader, this would most likely be mankind.

Freud's theory may be a plausible rendering of a primeval democratization of sorts among savages, allowing for more frequent and evenly distributed procreation. But it fails as a theory of the origin of religion, when tested on the great variety of beliefs and rituals around the world.

Not only that. Even in the highly unlikely case of the worship of a god stemming from an ancient need to make amends, the theory gives few tools for further understanding. It is a fait-accompli, a dead-end about which one can say little more than that it belongs to the past and therefore it can't be changed.

Freud is remarkably uninterested in finding some kind of cure for it, a way for mankind out of this emotional prison. He is only interested in showing that the Oedipus complex at the root of it is omnipresent, if not omnipotent. It is his baby, and he protects it vigorously. In more ways than one, it is his religion.

The Individual Versus the Collective

Freud's theories about religion, ritual, and myth have added little to the research in those fields. In the literature on those subjects, his theories are mentioned in passing as oddities that would have been forgotten if they came from a lesser-known figure than the father of psychoanalysis.Still, Freud's view may deserve additional considerations. Religion has been an integrated part of human life as far back as we can see, and the role it has played might need tools like those of Freud to be understood. It cannot be explained by instinct alone. The instruments of psychology and sociology need also be applied.

As for Freud, biology plays a significant part in his theory, which is unexpected coming from a psychologist. In his view, the human psyche — at least the male one — is driven by animalistic instincts and how they are expressed in matters of procreation. Man remains a primitive beast, a misfit in whatever culture he lives. Freud saw that as the main source to mental discomfort and illness.

In Moses and Monotheism, he makes the clear distinction between the individual and the collective perspective, stating that the psychopathology of human neurosis belongs to individual psychology, "whereas religious phenomena must of course be regarded as a part of mass psychology."[30]

This is evident in the structure and practice of most religions. They regulate how the individual should behave in order to comply with the demands of the group. In this way, religions are social laws, with the claim of having a higher than human justification. They are also, with their rituals and myths, instruments by which the individual gets some aid in adapting to them.

This function of religion, to which Freud was no stranger, is less likely to be adequately researched within the field of psychology, though, than for example in social anthropology, which deals with human behavior in the concrete setting of daily social life.

Notes

- Sigmund Freud, Moses and Monotheism (Der Mann Moses und die monotheistische Religion), transl. Katherine Jones, Letchworth 1939, p. 94. ↑

- Ibid., p. 130. ↑

- Ibid., pp. 130f. ↑

- Ibid., p. 132. ↑

- Ibid., p. 134. ↑

- Ibid., p. 129. ↑

- Ibid., p. 118. ↑

- Ibid., p. 129. ↑

- Ibid., p. 136. Credo quia absurdum: I believe because it is absurd. ↑

- Ibid., p. 137. ↑

- Ibid., p. 151. ↑

- Ibid., pp. 152f. ↑

- Ibid., p. 157. By phylogenetic Freud means something "pertaining to racial development." Ibid., p. 217. ↑

- Ibid., p. 158. ↑

- Ibid., p. 160. ↑

- Ibid., p. 161. ↑

- Ibid., p. 41. Ikhnaton is usually spelled Akhenaton or Akhenaten, and accordingly Aton is often spelled Aten. ↑

- Ibid., p. 105. ↑

- Ibid., p. 98. ↑

- Ernst Sellin, Mose und seine Bedeutung für die israelitisch-jüdische Religionsgeschichte, Leipzig 1922. ↑

- Freud, Moses and Monotheism, p. 98. The Midianites are mentioned in Genesis 25:1-4 as descendants of Abraham's son Midian. Exodus 2:15-21 has Moses flee to the land of Midian, where he marries a daughter of the priest. ↑

- Ibid., pp. 102f. ↑

- Ibid., p. 139. ↑

- Josef Breuer & Sigmund Freud, Studies in Hysteria, transl. A. A. Brill, New York 1936 (originally published in German 1895), p. v. ↑

- Freud, Moses and Monotheism, pp. 138f. ↑

- Ibid., p. 141. ↑

- Matthew 27:46 and Mark 15:34, King James Bible. ↑

- Freud, Totem and Taboo, p. 246. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Freud, Moses and Monotheism, p. 117. ↑

Sigmund Freud on Myth and Religion

1: Introduction

2: Totem and Taboo

3: The Future of an Illusion

4: Civilization and Its Discontents

5: Moses and Monotheism

6: The Stubborn Mind

Freudians on Myth and Religion

Introduction

Sigmund Freud

Freudians

Karl Abraham

Otto Rank

Franz Riklin

Ernest Jones

Oskar Pfister

Theodor Reik

Géza Róheim

Helene Deutsch

Erich Fromm

Literature

This text is an excerpt from my book Psychoanalysis of Mythology: Freudian Theories on Myth and Religion Examined from 2022. The excerpt was published on this website in February, 2026.

MYTH

Introduction

Creation Myths: Emergence and Meanings

Psychoanalysis of Myth: Freud and Jung

Jungian Theories on Myth and Religion

Freudian Theories on Myth and Religion

Archetypes of Mythology - the book

Psychoanalysis of Mythology - the book

Ideas and Learning

Cosmos of the Ancients

Life Energy Encyclopedia

On my Creation Myths website:

Creation Myths Around the World

The Logics of Myth

Theories through History about Myth and Fable

Genesis 1: The First Creation of the Bible

Enuma Elish, Babylonian Creation

The Paradox of Creation: Rig Veda 10:129

Xingu Creation

Archetypes in Myth

About Cookies

My Other Websites

CREATION MYTHS

Myths in general and myths of creation in particular.

TAOISM

The wisdom of Taoism and the Tao Te Ching, its ancient source.

LIFE ENERGY

An encyclopedia of life energy concepts around the world.

QI ENERGY EXERCISES

Qi (also spelled chi or ki) explained, with exercises to increase it.

I CHING

The ancient Chinese system of divination and free online reading.

TAROT

Tarot card meanings in divination and a free online spread.

ASTROLOGY

The complete horoscope chart and how to read it.

MY AMAZON PAGE

MY YOUTUBE AIKIDO

MY YOUTUBE ART

MY FACEBOOK

MY INSTAGRAM

STENUDD PÅ SVENSKA

Stefan Stenudd

About me

I'm a Swedish author of fiction and non-fiction books in both English and Swedish. I'm also an artist, a historian of ideas, and a 7 dan Aikikai Shihan aikido instructor. Click the header to read my full bio.

Archetypes of Mythology

Archetypes of Mythology Psychoanalysis of Mythology

Psychoanalysis of Mythology