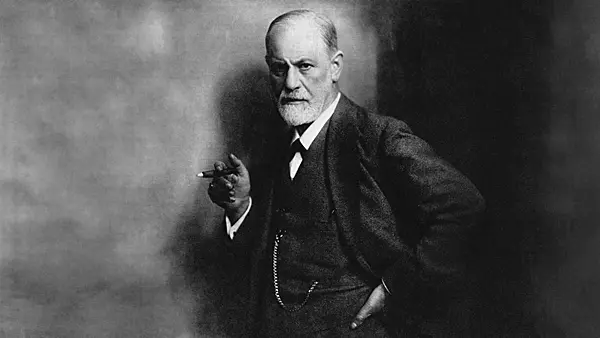

Sigmund Freud:

|

by Stefan Stenudd |

In The Future of an Illusion, Freud confirms his theory of the Oedipus complex being at the root of religion, but he also recognizes causes and effects that have a wider scope, such as the human need to tackle fear of the unknown, discussed above. In particular, "the painful riddle of death, against which no medicine has yet been found, nor probably will be."[1]

Enemies of Civilization

Freud describes the human condition as one of suffering from the tension between nature and civilization.[2] It is against the uncertainties and difficulties of the former that the latter is a guard. Still, Freud states firmly, "every individual is virtually an enemy of civilization."[3]This animosity towards the very thing that can improve life beyond what nature alone would allow, Freud explains as caused by the suppression of human urges and instincts. As for those urges, Freud's perception of human nature is not flattering: "Among these instinctual wishes are those of incest, cannibalism and lust for killing."[4] It is to appease people, in spite of this restraint, that religious ideas have taken their forms. According to Freud, the gods (now he speaks of a plural) have three major functions:

The gods retain their threefold task: they must exorcize the terrors of nature, they must reconcile men to the cruelty of Fate, particularly as it is shown in death, and they must compensate them for the sufferings and privations which a civilized life in common has imposed on them.[5]

Freud also describes a development of the roles of gods, as humans got to understand more of the world around them. Many phenomena of nature showed to be autonomous, in no need of continuous divine activity. So, the gods were focused on their third task, helping people deal with the frustration of conforming to civilization. This was mainly a question of morality, since it dealt not only with man's imperfections but also with those of civilization. The order imposed by civilization was on divine decree:

Everything that happens in this world is an expression of the intentions of an intelligence superior to ours, which in the end, though its ways and byways are difficult to follow, orders everything for the best — that is, to make it enjoyable for us.[6]

Therefore, obedience towards such a deity would be the only way to have a life as pleasant as possible. At least, that was the idea. Freud shows little trust in it actually having worked out well:

It is doubtful whether men were in general happier at a time when religious doctrines held unrestricted sway; more moral they certainly were not.[7]

Towards Science

The development of religion and then away from it, Freud compares to childhood needs and growing out of them. The comfort of religious beliefs belonged to primitive man of the distant past, like children need to have faith in being protected by their parents — especially, if not exclusively, by their father. At length, though, mankind needs to replace religion with science and leave those childhood beliefs behind.He states that this is happening, at least in Europe and in "the higher strata of human society."[8] As for the rest of the people, he doesn't have very high hopes:

Probably a certain percentage of mankind (owing to a pathological disposition or an excess of instinctual strength) will always remain asocial; but if it were feasible merely to reduce the majority that is hostile towards civilization to-day into a minority, a great deal would have been accomplished — perhaps all that can be accomplished.[9]

As an example of how it can still go wrong, he mentions the "monkey trial" at Dayton, Tennessee, in 1925. A science teacher was prosecuted for teaching that "man is descended from the lower animals."[10] Freud mentions nothing more about the case, in which the teacher John Thomas Scopes was fined $100. But in an appeal, the fine was removed since its size had been decided incorrectly in the previous court.[11]

Freud's essay is mainly an argument for society to leave the illusions of religion behind, and turn its trust to science. In spite of glitches like the "monkey trial" he does have hope for humanity growing out of this infancy:

The voice of the intellect is a soft one, but it does not rest till it has gained a hearing. Finally, after a countless succession of rebuffs, it succeeds. This is one of the few points on which one may be optimistic about the future of mankind, but it is in itself a point of no small importance.[12]

He ends his essay with a reference to its title:

No, our science is no illusion. But an illusion it would be to suppose that what science cannot give us we can get elsewhere.[13]

What he hopes for is that the future of the religious illusion will be short. As for the origin of the deity to fulfill the above-mentioned comforts, Freud remains with his theory from Totem and Taboo of a primeval patricide:

Religion would thus be the universal obsessional neurosis of humanity; like the obsessional neurosis of children, it arose out of the Oedipus complex, out of the relation to the father.[14]

He would stick to his theory also in his last book, Moses and Monotheism, published the same year he died. He was nothing if not persistent.

Nature versus Civilization

Freud claimed that the conflict between nature and civilization was the reason for human discomfort and led to — among other things — the emergence of religion. But nature and civilization are not opposites.Civilization is not an artifact born out of some brilliant or vicious mind of the past. It is not separate from nature, but has occurred within it, so to speak naturally. All humans, as far back as we can trace, have formed societies increasing in complexity over time — often in rigidity, as well. That is what our species does. It is in our nature.

Ours is far from the only species doing that. Look at the intricacies of how ants and bees are organized, how herds of buffalo move in unison, and great flocks of birds form patterns as they fly through the sky. Any animal species, where the individuals do not live in absolute solitude, is organized in more or less complex societies to which they adapt as a matter of instinct.

Civilization is part of nature. That does not mean we adapt to it without friction and frustration. Surely not. But very few of us would prefer to live outside it or see it totally ruined. Nothing would be more frustrating to us than to be excluded from it.

Even Freud's essay hints at it, when discussing why suppressed classes accept unfair treatment in a society where only few profit from it. He thinks it must be because the masses are "emotionally attracted to their masters" and "see in them their ideals." Without some such kind of explanation, "it would be impossible to understand how a number of civilizations have survived so long in spite of the justifiable hostility of large human masses."[15]

There may very well be other reasons for the suppressed masses accepting their situation, such as brute force in the hands of their oppressors. But it should also be taken into account that they are content, because they are themselves defenders and not enemies of civilization.

That is indeed what history shows us. Most members of any society are defenders of it, not enemies to it.

Incest, Cannibalism, and Killing

People are also defenders of the values and regulations their society professes. Few would indulge in incest, cannibalism and killing, nor would they approve of others doing so.As for cannibalism, or with a fancier word anthropophagy, civilization in the meaning of a regulated society is not a perfect safeguard against it. Except for occasions of starvation in crisis situations and the rare examples of criminal cannibalism committed by individuals, the instances of cannibalism examined by anthropologists and historians indicate that it was at the time socially accepted behaviors within those groups. Cannibalism was not only accepted in those situations, but encouraged, if not demanded in ritualistic habits. Such civilizations promoted cannibalism instead of suppressing it.[16]

As for killing, it may be illegal for individuals in most civilizations, but it is done collectively in quantities widely surpassing any one individual's urge or ability. The capital punishment, wars, and even genocides, are all inventions of civilization. Our present society is still very far from putting a stop to it. Instead, we have become ever more efficient at it.

Freud wrote his essay in 1927, which was a period when Europe had gone through a war so terrible that a repetition was unthinkable. But just a few years later, that had changed. And still today, nations arm themselves for annihilation. Our species would be safer from itself if we were unable to form civilizations.

It can be argued that these terrible shortcomings of civilization may be due to its acceptance, sometimes even encouragement, of the worst sides of man. If our species is by nature brutal, we should not be surprised if our civilization is, as well. But if that is the case, Freud's theory offers no solution. It would instead mean that civilization is not immune to what he regarded as our dreadful nature. Instead of man being reformed by society, he would simply form it to his liking. So, we would do neither better nor worse without it. There is no guarantee that civilization will be civilized.

Incest is a somewhat different matter, since it does not necessarily mean brutalization by one person of another. It might also be consensual. Still, it is condemned in most societies and has been for very long. As mentioned earlier, Freud theorized about it in Totem and Taboo, where he claimed that the taboo of incest stems from the Oedipus complex.

But there are anomalies in civilization's attitude towards incest and inbreeding. It is a matter of how far to take it. Many societies tend to frown upon finding a mate outside of it, even outside one's own sub-group within that society. Those sub-groups can be quite narrow, involving age, ethnicity, class, and what-not. Aristocrats and royalties tend to restrict marriage and procreation to the few of their own stratum. Especially in the case of royalties, it can become quite close to inbreeding.

The whole idea of mating within one's own kind, particularly upheld by the ruling classes of many societies, is incestuous at its core. Still, it is regarded as very civilized, indeed.

So, it can just as easily be said that civilization increases the occurrences and severity of incest, cannibalism and killing, instead of preventing them. Still, we tend to cherish our civilization — though certainly not because of these tendencies. Freud is not alone in seeing the benefits of an orderly society. We can all see it. To the masses as well as to their rulers, civilization is a good thing, in spite of its in some cases ghastly shortcomings.

Solace Instead of Fear

Of course, our willing commitment to civilization does not necessarily disprove Freud's idea about civilization developing in such a way that man's frustration towards it made religion arise as a kind of remedy. But it puts in question his statement that this would be universal and unavoidable because of some fundamental conflict between nature and civilization.Since the formation of civilizations is more natural for us than having none, as history has proven, this tendency alone cannot explain what appears in these civilizations. Each phenomenon must be examined for what it implies about any underlying mechanism, and that may very well differ from one society to another.

Freud's claim that the illusion of a divine origin to the rules of society was to increase human trust in them is not far from what Critias in Ancient Greece suggested, as mentioned previously: Gods were invented to scare people into obedience of the laws. But where Critias speaks of fear, Freud points to solace. Religion gave mankind the illusion of fate being governed by a higher wisdom, leading ultimately to something good and fair. People could put faith in their god and would no longer need to live in fear of the unknown and everything over which they had no control. It was all taken care of by a benevolent force, who was the greatest of all.

This applies easier to monotheism than to other forms of religion, but it can be traced in many mythologies and beliefs around the world. It also connects to James G. Frazer's idea that people in the past tried magic to control what could not be controlled by physical action, and when that failed, they turned to prayer and worship. The search for tools to handle the perils of life has been going on as far back as we can trace, and in every culture.

Of course, this strife is not limited to the threats of unpredictable fate, the workings of which are beyond our understanding. It is the same with the everyday difficulties of finding food, avoiding risks to our well-being, and so on. It's the struggle to survive.

We keep wrestling with our fears of the known as well as the unknown. We keep developing our tools — both those of evident use and those putting trust in superstition. As soon as a threat is defined, whether rightly or wrongly, we work on avoiding it and do not stop until we succeed. It is an urge that never leaves us.

Probably it is also the core incentive behind humans gathering into groups and continuing to expand and advance these groups into civilizations. We do it primarily to survive, secondarily to survive comfortably.

So far, it is only the ultimate threat that defies our efforts, also pointed out by Freud in his essay: There is no escaping death. We have succeeded in prolonging our life expectancy, especially during the last couple of centuries, but just by so much. We keep trying, with frenzy, by means of science as well as precautions on a personal level. But there is no changing the outcome. We can only postpone it, and even that is quite uncertain.

This has been known for as long as we have been conscious beings. If religion is born out of fear and the need for solace, death must be its major objective. We need to overcome the fear of it, or every life is one of panic increased by time, and we need solace afore the fact that death will come, no matter what.

Not that every mythology is doing a very good job at it, as discussed previously. In many of them, death is still to be dreaded, either because of what horrors await or because nothing is stated about it.

The two religions dealing substantially with the afterlife, Christianity and Islam, promise good tidings for the faithful. After death, people will get what they deserve, and for the believers the prospects are very promising. Might that have added to the successful spread of those two religions in the world? It has certainly always been a central element of their teaching and a central conviction among their believers.

This may also be the main reason for those religions keeping vast numbers of followers, in spite of scientific progress making those beliefs increasingly questionable. Freud's hope for the illusion coming to an end is yet to come true.

The simple fact that science cannot present the same solace, afore the bitter end of every life, is why it can't replace religion. What life is really like is not what we want it to be. So, a more attractive alternative — no matter how imaginary — is not easily abandoned.

Freud was aware of this, but he underestimated its persistence.

Notes

- Sigmund Freud, The Future of an Illusion (Die Zukunft einer Illusion, 1927), transl. James Strachey, New York 1961, p. 16. ↑

- Freud uses the German word Kultur, which can be translated as both culture and civilization, depending on the context. Ibid., 4. ↑

- Ibid., p. 6. ↑

- Ibid., p. 10. ↑

- Ibid., p. 18. ↑

- Ibid., p. 19. ↑

- Ibid., p. 37. ↑

- Ibid., p. 38. ↑

- Ibid., p. 9. ↑

- Ibid., p. 38. ↑

- Scopes Trial, Wikipedia. ↑

- Freud, The Future of an Illusion, p. 53. ↑

- Ibid., p. 56. ↑

- Ibid., p. 43. ↑

- Ibid., p. 13. ↑

- For anthropological studies of cannibalism, see Paula Brown & Donald F. Tuzin (ed.), The Ethnography of Cannibalism, Washington D.C. 1983. ↑

Sigmund Freud on Myth and Religion

1: Introduction

2: Totem and Taboo

3: The Future of an Illusion

4: Civilization and Its Discontents

5: Moses and Monotheism

6: The Stubborn Mind

Freudians on Myth and Religion

Introduction

Sigmund Freud

Freudians

Karl Abraham

Otto Rank

Franz Riklin

Ernest Jones

Oskar Pfister

Theodor Reik

Géza Róheim

Helene Deutsch

Erich Fromm

Literature

This text is an excerpt from my book Psychoanalysis of Mythology: Freudian Theories on Myth and Religion Examined from 2022. The excerpt was published on this website in February, 2026.

MYTH

Introduction

Creation Myths: Emergence and Meanings

Psychoanalysis of Myth: Freud and Jung

Jungian Theories on Myth and Religion

Freudian Theories on Myth and Religion

Archetypes of Mythology - the book

Psychoanalysis of Mythology - the book

Ideas and Learning

Cosmos of the Ancients

Life Energy Encyclopedia

On my Creation Myths website:

Creation Myths Around the World

The Logics of Myth

Theories through History about Myth and Fable

Genesis 1: The First Creation of the Bible

Enuma Elish, Babylonian Creation

The Paradox of Creation: Rig Veda 10:129

Xingu Creation

Archetypes in Myth

About Cookies

My Other Websites

CREATION MYTHS

Myths in general and myths of creation in particular.

TAOISM

The wisdom of Taoism and the Tao Te Ching, its ancient source.

LIFE ENERGY

An encyclopedia of life energy concepts around the world.

QI ENERGY EXERCISES

Qi (also spelled chi or ki) explained, with exercises to increase it.

I CHING

The ancient Chinese system of divination and free online reading.

TAROT

Tarot card meanings in divination and a free online spread.

ASTROLOGY

The complete horoscope chart and how to read it.

MY AMAZON PAGE

MY YOUTUBE AIKIDO

MY YOUTUBE ART

MY FACEBOOK

MY INSTAGRAM

STENUDD PÅ SVENSKA

Stefan Stenudd

About me

I'm a Swedish author of fiction and non-fiction books in both English and Swedish. I'm also an artist, a historian of ideas, and a 7 dan Aikikai Shihan aikido instructor. Click the header to read my full bio.

Archetypes of Mythology

Archetypes of Mythology Psychoanalysis of Mythology

Psychoanalysis of Mythology